Mom’s Phone Call Helps Uncover Oldest Long-Necked Dinosaur on Record

Mom’s Phone Call Helps Uncover Oldest Long-Necked Dinosaur on Record

There’s a lot missing from the fossil record when it comes to the earliest dinosaurs. That makes the discovery of not one but three well-preserved skeletons, two of them nearly complete, all the more significant. Even better: The new species they represent, Macrocollum itaquii, is the oldest long-necked dinosaur known. The trio gives us a snapshot of a lineage in the transition from small and swift meat-eaters to the mightiest animals ever to walk Earth.

Thanks to a phone call from a scientist’s mom, paleontologists have uncovered the oldest long-necked sauropod dinosaur on record.

The tale began in 2012 when Estefânia Temp Müller called her son, Rodrigo Temp Müller, a paleontologist in Brazil. Estefânia told her son that his uncle had found some fossils on a rural property in Agudo, in southern Brazil. This motherly tip soon led to a major find

Uncovered at the Wachholz site near Agudo in Brazil’s southernmost state, Rio Grande do Sul, the three individuals described as M. itaquii are most generally classified as sauropodomorphs.

The lineage emerged at the very Dawn of Dinos, more than 230 million years ago. Back then, the very first sauropodomorphs were two-legged flesh-eaters that were not particularly impressive in size.

Then very quickly, at least chronostratigraphically speaking, the sauropodomorph lineage, well, morphed.

They evolved into plant-eaters with a distinctive body plan: small head, long neck, a large body that was carried on four column-like legs, and a spectacularly long tail.

The animals also got super-sized, ultimately maxing out with the titanosaurs, which grew up to 120 feet in length.

Alas, paleontologists have long been without good evidence for how that transition occurred. That’s changing — 2018, in particular, has been a great year for new early sauropodomorphs, such as Ingentia prima and Ledumahadi mafube. Now, from southern Brazil emerges perhaps the most exciting early sauropodomorph find of the year.

Brazil’s southernmost state of Rio Grande do Sul is home to the fossiliferous Wachholz site, near Agudo, where Macrocollum itaquii was found.

Meet Macrocollum itaquii

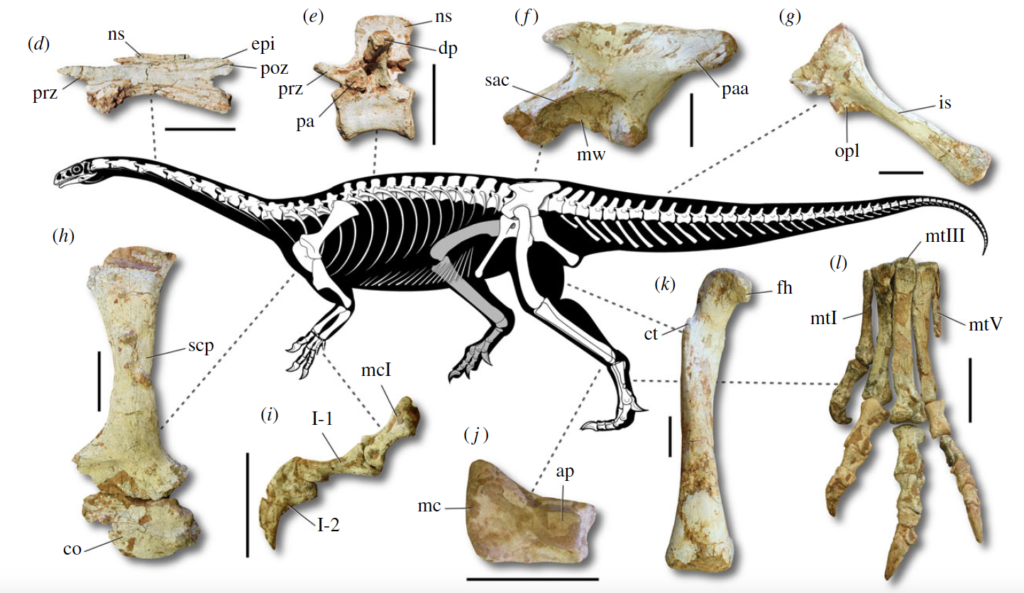

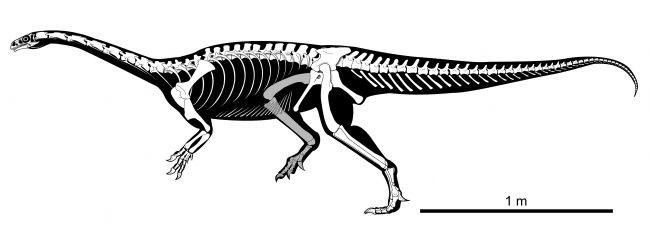

Paleontologists unearthed three skeletons preserved together in rock dated to the early Norian Age of the Triassic Period, putting the fossils’ age at about 225 million years.

The fact that the animals were found in close proximity provides, say the researchers, the earliest evidence of social behavior in the sauropodomorph lineage.

One of the skeletons was missing its head and parts of its neck, but the other two were nearly complete. The bones of one of the two were still articulated, preserved as they were when the animal died.

The early sauropodomorph has a number of unique transitional traits that show evolution in action. While the earliest sauropodomorphs did not have elongated necks, Macrocollum does, suggesting it was already adapted to eating vegetation growing well off the ground.

The elongation can be seen in individual vertebra: Its fourth neck vertebra is more than twice as long, proportionally, like that of an earlier Brazilian sauropodomorph, Buriolestes schultzi, which is about 8 million years older. Overall, Macrocollum’s neck-to-body ratio is about twice that of Buriolestes.

Buriolestes and other earlier sauropodomorphs also have back legs with tibia that are longer than the femur (thigh bone), a proportion typically seen in animals that run.

In Macrocollum, however, that proportion is reversed: its femur is the long bone. Its foot, however, still retains several characteristics of fleet-footed animals — anatomical traits that were gradually abandoned in favor of the elephant-like feet of later sauropods.