This Ancient Mummy May Be The Oldest-Known Victim Of Heart Failure

This Ancient Mummy May Be The Oldest-Known Victim Of Heart Failure

A 3,500-year-old mummy is changing the way scientists think about heart disease.

A research team at the international congress of egyptology in Florence reported that the oldest cases of acute decompensated heart failure have been found in 3,500 years of mummified remains.

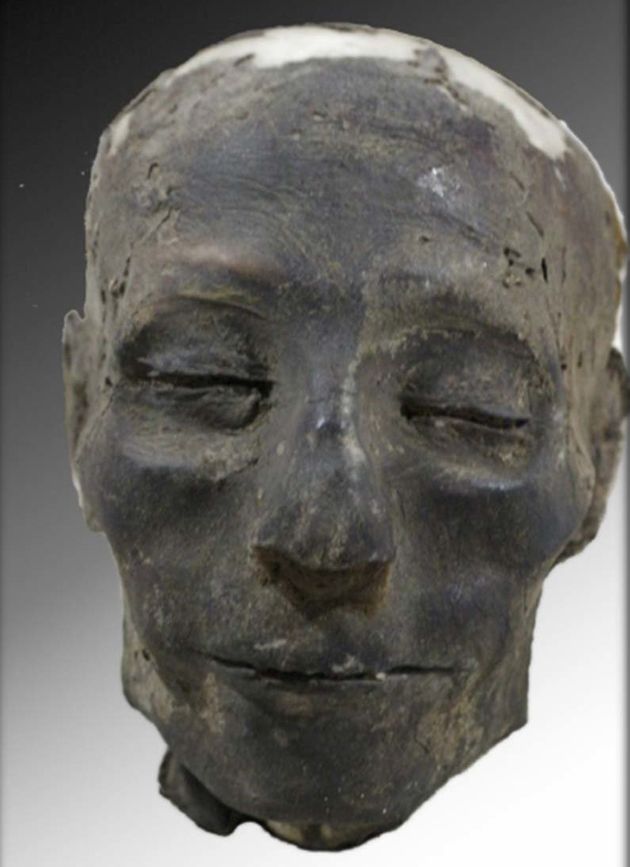

In 1904, the Italian Egyptologist Ernesto Schiaparelli found the remains in a plundered tomb in the Queen Valley, Luxor, and now are located in the Egyptian Museum in Turin, which consists of one head and canopic jars containing internal organs.

They belong to an Egyptian dignitary named Nebiri, the “Chief of the stables” who lived under the reign of Pharaoh Thutmose III of the 18th Dynasty (1479-1424 BC).

“The head is almost completely unwrapped, but in a good state of preservation. Since the canopic jar inscribed for Hapy, the guardian of the lungs, is partially broken, we were allowed direct access for sampling,” Raffaella Bianucci, an anthropologist in the legal medicine section at the University of Turin, told Discovery News.

She investigated the mummified remains with researchers from the Universities of Turin, Munich and York.

Detailing the findings at the conference, Bianucci reported that Nebiri was middle aged — 45 to 60 years old — when he died and that he was affected by a severe periodontal disease with massive abscesses, as revealed by Multidetector Computed Tomography (MDCT) and three dimensional skull reconstruction.

The scans showed there was a partial attempt at excerebration (removal of the brain), but a considerable amount of dehydrated brain tissue is still preserved. Linen is packed in the inner skull, eyes, nose, ears, mouth and even fill the cheeks. The researchers also detected evidence of calcification in the right internal carotid artery, consistent with a mild atherosclerosis.

“We saw only a tiny fleck of calcium. Since the rest of the corpse is missing, it is impossible to establish whether there was calcification in other artery walls,” she added.

Most interestingly, the histology of the lung performed by Andreas Nerlich, professor at the department of pathology at Ludwig-Maximilians-University in Munich, Germany, revealed the presence of “heart failure” cells. A pulmonary edema, which is fluid accumulation in the lungs’s air sacs, was also identified.

“When the heart is not able to pump efficiently, blood can back up into the veins that take it through the lungs. As the pressure increases, fluid is pushed into the air spaces in the lungs,” Bianucci explained.

Since histochemical staining ruled out other possible diseases including tuberculosis, granulomas and acid-fast bacilli indicating mycobacterial infections, the researchers concluded that Nebiri possibly died from acute decompensation of chronic left-sided heart failure, which is a frequent consequence of chronic heart disease.

“Our finding represents the oldest evidence for chronic heart failure in mummified remains,” Bianucci said.

Valvular disease, ischemia, metabolic disorders of the heart muscle, or chronic hypertension are among the causes for the disorder. In Nebiri’s case, the researchers believe chronic hypertension is the best candidate.

Currently, over 20 million people worldwide, mainly over 65, are affected by chronic heart failure. “A systematic analysis of canopic jar content could help establish whether the disease was more frequent in our ancestors or its prevalence increased in modern times,” Bianucci said.

The elaborate mummification technique played a crucial role in diagnosing the cause of death, according to the researchers. “The level of preservation is outstanding and easily equals the standard seen with royals of the time,” Egyptologist Joann Fletcher, professor at the University of York’s Department of Archaeology, told Discovery News.

Chemical analysis of the compounds used to treat Nebiri’s corpse revealed a relatively high quality of mummification.

“It was a complex mixture of an animal fat or plant oil, a balsam/aromatic plant, and non-native conifer resin and pistacia resin. The last three ingredients contain strongly antibacterial compounds, so would certainly have helped preserve his body and lungs,” Stephen Buckley, an archaeological chemist at the University of York in England, told Discovery News.

Current research is now focusing on Nebiri’s facial reconstruction, which is being carried out by Tobias Houlton and Christopher Rynn from the University of Dundee, UK.