Saharan remains may be evidence of first race war, 13,000 years ago

Saharan remains may be evidence of first race war, 13,000 years ago

The remains of humans killed 13,000 years ago in what scientists believe to be the oldest known race war are today due to going on display at the British Museum in London.

Two skeletons from an 11,000BC massacre in the Sahara desert that killed at least 26 people will be shown in the new gallery of Ancient Egypt, alongside the flint-tipped weapons they were killed with.

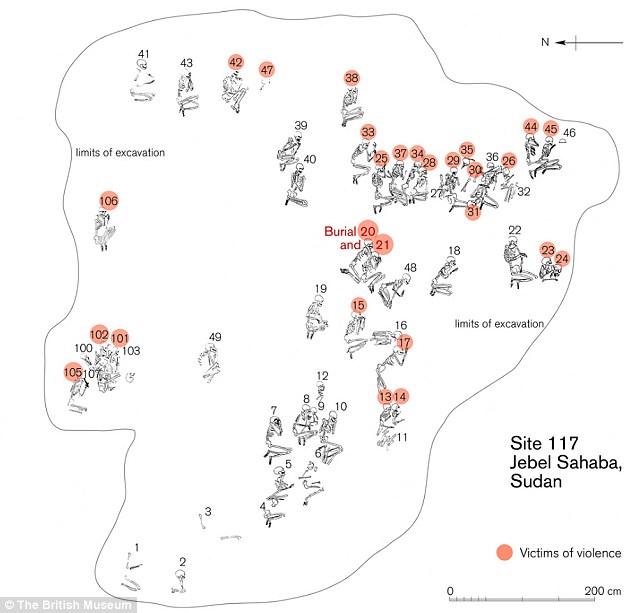

French scientists worked with the museum to investigate dozens of skeletons found grouped together in the Jebel Sahaba cemetery, one of the earliest organized burial grounds in the 1960s on the east bank of the Nile, northern Sudan.

They believe that the remains of the 60 individuals found-about half of which had cut marks on their bones-represent the first communal violence between groups.

Fighting probably broke out because of the environmental disaster of the Ice Age, which caused the attackers and victims to live together in a smaller area, the experts explained.

Renee Friedman, the museum’s curator of early Egypt, told The Times that the attackers and victims were hunter-gatherers who usually avoided violence by moving on when a certain area became overcrowded.

But she believed that the cold and dry conditions of the Nile valley around that time caused a ‘population crisis’, as more people moved to the same area surrounded by desert.

She said: ‘Things were probably very tight, so we think that people started picking on one another.’

The museum acquired the remains in 2002 when they were donated by Fred Wendorf, an American archaeologist who excavated the site in the 1960s.

At least 60 individuals were found and examined using modern technology. One body was found with 39 pieces of flint from arrows and other flint-tipped weapons, Dr Friedman said.

As well as the human remains, the display will include flint arrowhead fragments and a healed forearm fracture, which was most likely sustained by a victim who was trying to defend himself during conflict.

Over the past two years, anthropologists from Bordeaux University have managed to find dozens of previously undetected conflict marks on the victims’ bones.

The British Museum scientists are now planning to research more about the victims themselves, including their gender, their age and their diet.

Meanwhile, according to The Independent, work carried out at Liverpool John Moores University, the University of Alaska and New Orleans’ Tulane University suggests these humans were part of the general sub-Saharan originating population, who were ancestors of modern Black Africans.

Dr. Daniel Antoine, a curator in the British Museum’s Ancient Egypt and Sudan Department, told the paper: ‘The skeletal material is of great importance – not only because of the evidence for conflict, but also because the Jebel Sahaba cemetery is the oldest discovered in the Nile valley so far.’