This 48-Million-Year-Old Fossil Has an Insect Inside a Lizard Inside a Snake

About 48 million years-ago a young snake died a few days after eating a lizard in a volcanic lake.

The lizard had just eaten a beetle that was still in its stomach, and the evidence of this ancient food chain has been preserved for millions of years.

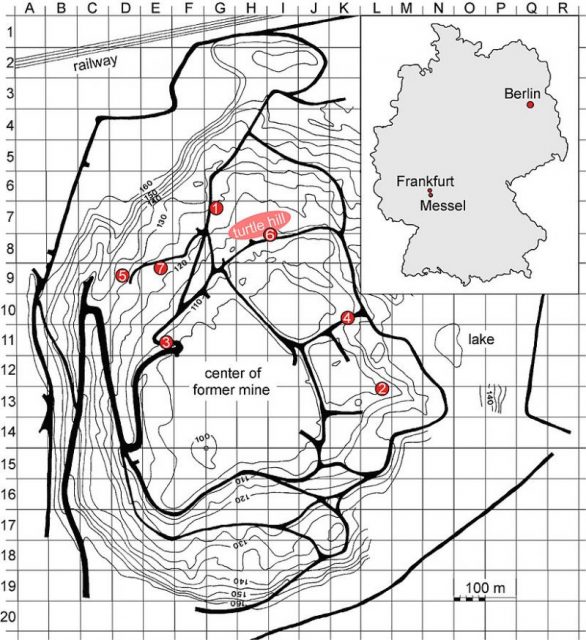

The unique fossil has now been uncovered by researchers digging in the Messel pit near Frankfurt.

Researchers excavating in the Messel pit near Frankfurt had now uncovered the rare fossil.

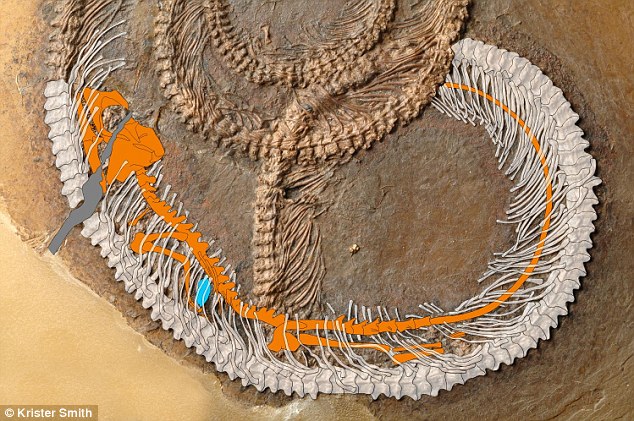

Dr. Krister Smith, from the Department of Messel Research said that, “in the year 2009, we have been able to recover a plate from the pit showing almost fully preserved snake.

‘ And as if this was not enough, we found inside the snake, a fossilized lizard, which in turn contained a fossilized beetle in its innards!’

Fossil food chains are extremely rarely preserved.

Only one other fossil like this has been found in the world.

Due to the excellent level of preservation at the Messel fossil site, leaves and grapes from the stomach of a prehistoric horse, pollen grains in a bird’s intestinal tract and remains of insects in fossilized fish excrements had previously been discovered there.

‘However, until now, we had never found a tripartite food chain – this is a first for Messel.’

Using a high-resolution computer imaging, Dr Smith and his colleague Agustín Scanferla from Argentina identified the species of both the snake and the lizard.

‘The fossil snake is a member of Palaeophython fischeri; the lizard belongs to Geiseltaliellus maarius, which has only been found at Messel to date,’ Dr Smith said.

The snake is 3.4 feet (103 centimetres) long, much smaller than other specimens of this species, which can reach 6.6 feet (two metres) or more. Dr Smith said the fossil was a juvenile of this relative of the modern-day boas.

The lizard was 20 centimetres from the head to the tip of its tail – and some of the snake’s ribs, which overlap the arboreal reptile, clearly indicate that the lizard is located inside the snake.

The lizard had the ability to shed its tail in case of danger, but did not lose it when it fell prey to the snake.

‘Unfortunately, we were unable to unambiguously identify the beetle – it was not well enough preserved to do so,’ Dr Smith said.

The small crawler offers insights into the previously barely known feeding behaviour of these lizards from Messel.

The stomachs of previously discovered reptiles only contained the remains of plants; the fact that the lizards also fed on insects indicates an omnivorous diet.

‘Since the stomach contents are digested relatively fast and the lizard shows an excellent level of preservation, we assume that the snake died no more than one to two days after consuming its prey and then sank to the bottom of the Messel Lake, where it was preserved,’ said Dr Smith.