AKTION T4 THE NAZI EUTHANASIA PROGRAMME THAT KILLED 300,000

AKTION T4 THE NAZI EUTHANASIA PROGRAMME THAT KILLED 300,000

Both before and during the Holocaust, the Nazi authorities carried out a massive but lesser-known program of targeted mass killing targeting some of the most vulnerable people under their control: the disabled.

Starting as a euthanasia program that eliminated disabled infants and children deemed unfit to live and expand in time for disabled adults and elderly people, the program ended in 1941 in the midst of protests from many quarters of German society.

But the mass killing machines that this program developed would not lie idle for a long time. These victims — as many as 300,000 of them in total — helped the Nazis to refine the methods they would soon have used to carry out the Holocaust.

The final solution’s “rehearsal” had no official name, and was only known in Germany at the head of the headquartered: 4 Tiergartenstraße, Berlin, which inspired the name Aktion T4.

The Roots Of The Aktion T4 Program

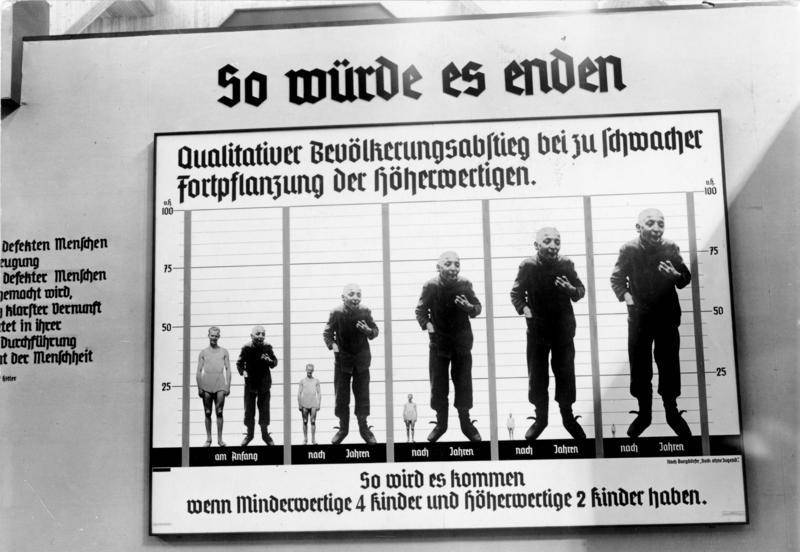

The ideological underpinnings of Aktion T4 were apparent in Nazi thinking from the party’s very beginnings. Nazi leaders had long preached the gospel of eugenics, calling for scientific control over Germany’s gene pool with the aim of improving it through state action.

In Mein Kampf, Adolf Hitler himself had spelled out the Nazi notion of “racial hygiene,” writing that Germany “must see to it that only the healthy beget children” using “modern medical means.” The Nazis believed this would produce Germans fit for the workforce, military service, and so on — while weeding out all others.

And as soon as the Nazis swept into power in 1933, they implemented laws that mandated sterilization for the physically and mentally disabled. It didn’t take much to become a victim of this program. Most victims were sent to be sterilized due to a vague diagnosis of “feeblemindedness,” while blindness, deafness, epilepsy, and alcoholism accounted for some of the other sterilizations.

All in all, the Nazis forcibly sterilized some 400,000 people. But once the war began in 1939, the Nazis’ plans for the disabled grew even darker.

The Test Case

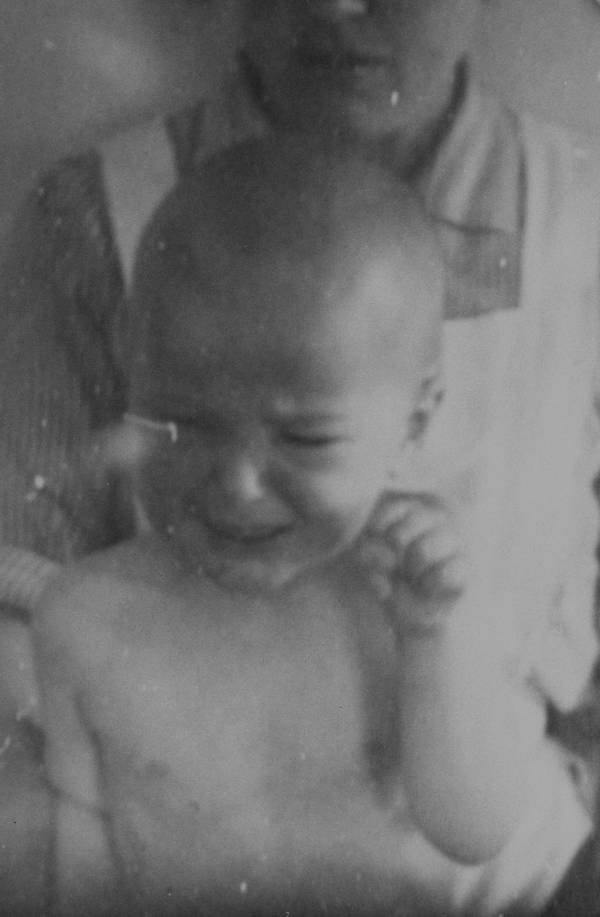

In early 1939, an odd letter arrived at the office of the Nazi Party Chancellery from a German man and Nazi loyalist named Richard Kretschmar. He was trying to contact Hitler directly in hopes of gaining clearance to legally euthanize his own son, Gerhard, who had been born just a few months earlier with severe and incurable physical and mental disabilities including missing limbs, blindness, and convulsions (the original medical records are lost and secondhand accounts vary).

Kretschmar asked Hitler to let them have this “monster” put down. Hitler then sent his own physician, Dr. Karl Brandt, to look into the case. On inspection, Brandt decided the diagnosis had been correct, that he was an “idiot,” and there was no hope for improvement. Thus Gerhard was killed by lethal injection on July 25, 1939. His death certificate stated the cause of death as “heart weakness.”

Having now broken the ice, Hitler and company immediately set into a motion a plan that would call for the killing of the physically and mentally disabled in Germany en masse.

Aktion T4 Is Born

British historians Laurence Rees and Ian Kershaw made the case that the Aktion T4 program’s rapid spread was typical of the chaotic nature of Hitler’s government. In their estimation, Hitler had only to speak about something generally before some ambitious subordinate would almost instantly cobble together a full-scale program from nothing.

The sudden expansion of the Aktion T4 program would seem to exemplify that notion. Within three weeks of the killing of Gerhard Kretschmar, a fully fleshed-out bureaucracy had sprung into existence and was issuing paperwork to doctors and midwives all over Germany.

Hitler had authorized the creation of the Reich Committee for the Scientific Registering of Hereditary and Congenital Illnesses, led by Brandt and Nazi Chief of the Chancellery Philipp Bouhler, among others. These men then put a deadly system into place.

Upon the occasion of every birth, an official would have to fill out a form that included a section for describing physical or other observed defects that the child might have. Three doctors would then review the forms – without any of them actually examining the patient themselves – and mark it with a cross if they thought the child should be killed.

Two-out-of-three crosses were enough to warrant the removal of the child from their home under the guise of helping them get medical attention and then killing them. Aktion T4 was born.

As fitting as it is to imagine the Third Reich spontaneously developing a huge killing program like this overnight, it’s actually more likely that the idea had been floating around for a while prior to the first killing.

In private, Hitler and other top Nazis were prone to complaining that Britain and America (which both had eugenics laws of their own) were far ahead of Germany in their efforts to weed out undesirables via euthanasia. Back in the mid-1930s, Hitler had reportedly told subordinates that he preferred killing to sterilization but that “Such a problem could be more smoothly and easily carried out in war.”

And now, with World War II underway, the time to kill had begun.

The Methods Of Aktion T4

Whether or not the killing of Gerhard Kretschmar was part of a larger plan, what followed was a massive operation unlike anything the world had ever seen.

By the summer of 1939, hundreds of infants and young children had been removed from homes and healthcare facilities across Germany and were transported to one of six sites: Bernburg, Brandenburg, Grafeneck, Hadamar, Hartheim, and Sonnenstein. These were working asylums, so there was nothing unusual about new patients arriving and being housed in secure wards at first.

Once there, the children would typically be given fatal doses of luminal or morphine. Sometimes, however, the method of killing wasn’t so gentle.

One doctor, Hermann Pfannmüller, made a specialty of gradually starving the children to death. It was, according to him, a more natural and peaceful way to go than a harsh chemical injection that stopped the heart.

In 1940, when his facility in occupied Poland was visited by members of the German press, he hoisted one starving child over his head and proclaimed: “This one will last another two or three days!”

“The image of this fat, grinning man, with the whimpering skeleton in his fleshy hand, surrounded by other starving children, is still clear before my eyes,” one observer from that visit later recalled.

On the same visit, Dr. Pfannmüller complained about getting bad press from “foreign agitators and certain gentlemen from Switzerland,” by which he meant the Red Cross, which had been trying to inspect his hospital for nearly a year at that point.

After the early days of the program, the scope of Aktion T4 was expanded to include older children and adults with disabilities who couldn’t care for themselves. Gradually, the net was cast wider and wider and the methods of killing became more standardized.

Eventually, victims were sent directly to a killing centre for “special treatment,” which by that point usually involved carbon monoxide chambers disguised as showers. Credit for inventing the “bath and disinfection” ruse goes to Bouhler himself, who suggested it as a means of keeping the victims quiet until it was too late.

High-ranking Nazis took note of this efficient method of killing and later put it to much wider use.

The Resistance

The Nazi Party had always had a difficult relationship with Germany’s religious community. It would be wrong to say they were forever at odds, but the church represented a separate, and largely independent, power system in the heart of what was fast becoming a dictatorship.

Early on, Catholic resistance to the Nazis led to the newly empowered party agreeing to hand over education of German children in Catholic states to the Church, while individual Protestant denominations gradually made their peace with Hitler. By about 1935, this culture war was dormant.

Or, it was, until news of the Aktion T4 program broke in 1940. Revelations about what was going on in the killing centres were bound to come out eventually, if only because the families of the victims all had nearly identical experiences: their child or disabled adult would be carted away by a charitable service working with the state, they’d get a few letters of the patient was able to write, and then there’d be a notification that their loved one had succumbed to measles and their body had been cremated as a health precaution.

No inquiries could be made and no visits were possible. It was inevitable that some families would eventually hear the same story from others and put two and two together, especially when the routine was the same across all six facilities.

Once people got wise, churches led the resistance to the Aktion T4 program by raising awareness, speaking out, and even distributing leaflets that brought the matter to the attention of many Germans for the first time.

The foreign press was even harsher on the Aktion T4 program.

In his 1941 book, The Berlin Diary, American Journalist William L. Shirer described Aktion T4 in a passage that began: “A word about a matter the Nazis would kill me over, if they knew I knew about it.” When the book was published and these words made it out of Germany, other American and British journalists did what they could but wartime secrecy largely kept the outside world in the dark.

The End Of The Aktion T4 Program

As a sop to the remaining pockets of resistance (and no doubt as a result of the fact that he had other things on his mind), Hitler finally agreed to halt the program in August 1941, after somewhere between 90,000 and 300,000 people had been killed. Virtually all of the victims were German or Austrian, and nearly half of them had been children.

But even after the ostensible halt of the killings in 1941, they eventually resumed and were simply folded into the larger program of the nascent Holocaust, making the true toll even harder to ever truly know.

This is only fitting considering that the ideologies, techniques, machinery, and personnel used in the Aktion T4 program would prove invaluable at the concentration camps of the Holocaust. In the words of the United States Holocaust Memorial and Museum:

The “euthanasia” program represented in many ways a rehearsal for Nazi Germany’s subsequent genocidal policies. The Nazi leadership extended the ideological justification conceived by medical perpetrators for the destruction of the “unfit” to other categories of perceived biological enemies, most notably to Jews and Roma (Gypsies).

And as was the case with the Holocaust as a whole, only some of the Nazis responsible for the Aktion T4 program ultimately faced justice.

Just after the war, Philipp Bouhler committed suicide after being captured. Meanwhile, the so-called Doctors’ trial of 1946-1947 saw the International Military Tribunal sentence several Nazi doctors to death for their role in the program (among other offences), including Dr. Brandt.

Dr. Pfannmüller was ultimately convicted for his role in 440 murders in 1951 and was sentenced to five whole years in prison. Later, he successfully appealed to reduce that to four years. He was released in 1955 and died quietly as a free man at his home in Munich in 1961.

Today, a memorial stands near the former site of the Aktion T4 program’s headquarters in Berlin where Nazi officials organized a mass killing like few the world has ever seen.

Subscribe to our newsletter!