America’s First Supermodel Died Alone in a Mental Asylum After 65 years

America’s First Supermodel Died Alone in a Mental Asylum After 65 years

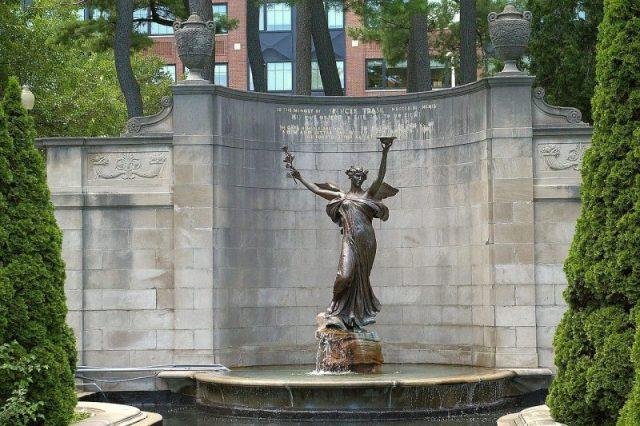

You may never have heard of Audrey Munson, but you’ve probably seen her face if you’ve spent any time in New York. Its similarity can be seen across the city, from Adolph Weinman’s golden figure on top of the Manhattan Municipal Building to the New York Public Library’s carved stone façade on Fifth Avenue.

Born in 1891, in Rochester, Audrey Munson is regarded as “America’s first supermodel.” She was stunningly beautiful and spent her youth posing for sculptors. While her beauty was eternalized in the hands of New York artists such as Isidore Konti, Daniel Chester French, Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, and many others, by the time she was 30, Munson was jobless.

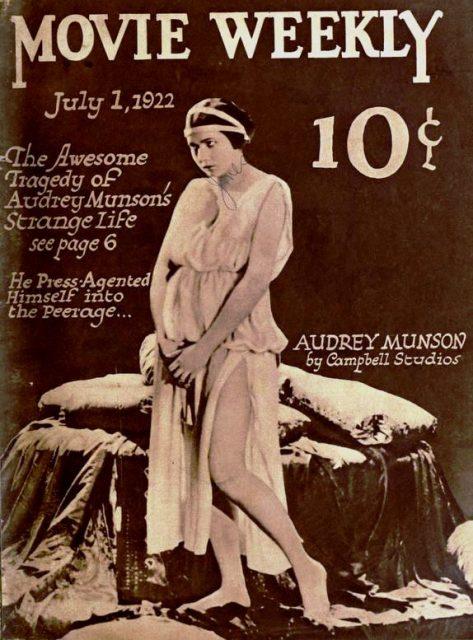

The interest in her faded away, and after an attempt for suicide in 1921, “Miss Manhattan” spent 65 years in a psychiatric asylum. Her longevity was a punishment for Munson who lived up to the age of 104, only to remember, in loneliness, how America desired her once upon a time.

When she was 5 years old, Munson got her fortune told by the Gypsy Queen Elza. She told her: “You shall be beloved and famous. But when you think that happiness is yours, its Dead Sea fruit shall turn to ashes in your mouth.“You, who shall throw away thousands of dollars as a caprice, shall want for a penny. You, who shall mock at love, shall seek love without finding.“Seven men shall love you. Seven times you shall be led by the man who loves you to the steps of the altar, but never shall you wed.”Audrey always believed the telling was a curse.

Her parents divorced when she was 8, and little Audrey remained living with her mother. Having aspirations to become an actress and chorus girl, at the age of 17, Munson moved to New York City with her mother.

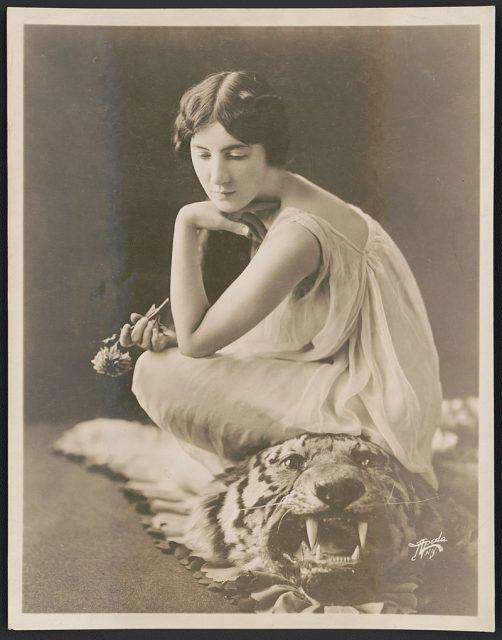

However, her limber figure and long bones, her symmetrical face with chiseled cheekbones, high brows, an almond jaw, perfectly straight neoclassical nose, and gray-blue eyes were first spotted by the photographer Felix Benedict Herzog, while she was window shopping. Herzog immediately invited her to pose for him in his studio in the Lincoln Arcade Building.

That was her gateway to fame, to becoming America’s first supermodel. Herzog introduced her to the people in the art world and very soon, artists started requiring her as a model for their work. It was the sculptor Isidore Konti who first asked her to pose naked. He claimed that for them, the artists, it doesn’t make such a great difference if the model is naked or all dressed up because they see only the work they do. Those words convinced her mother, and Audrey posed nude. After that, every famous artist wanted her to pose for them.

From Miss Manhattan to Panama-Pacific girl. In 1915, Munson posed as the model for more than half of the sculptures displayed at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition, the World Fair held in San Francisco, which earned her the name Panama-Pacific Girl.

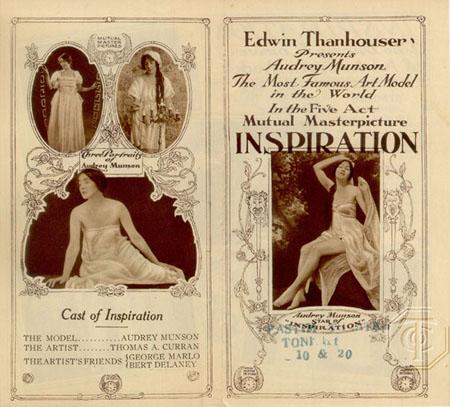

That same year Audrey received her first role in the silent movie Inspiration, about a sculptor who is in search of the perfect model to inspire him. Unfortunately, it is believed that all copies of the movie are lost. How much Audrey was desired on the film screen is indicated by the fact that actual actresses were chosen as her doubles to do the acting part while she only appeared in the nude scenes.

In the following year, 1916, Munson performed in another movie, Purity, which is the only surviving movie of all four she appeared in. It was rediscovered in 1993, in a French pornography collection, and later obtained by the French national cinema archive.

This gave her hope for her acting aspirations, so between 1915 and 1917, Miss Manhattan moved to Santa Barbara, hoping to pursue a movie career. However, without any success, Munson returned to her sculptors in New York. Of course, there were 7 men who fell in love with her, and maybe more, but she never fell in love with any of them. Instead, she got involved in their love fantasies and unwillingly became part of crimes she probably didn’t anticipate nor want.

In 1917, Hermann Oelrichs Jr., an heir to the Comstock Lode, and the richest bachelor in America at the time proposed to Munson, and her mother was very supportive of the idea. What happened next is lost to history, but it is known that in 1919, Munson sent a letter to the U.S. State Department, accusing Oelrichs of being a member of a pro-German network which conspired to sabotage her film career. She also wrote about her plans for leaving for England and restarting her acting career there.

After that, Audrey and her mother lived in a boarding house owned by Dr. Walter Wilkins who eventually fell in love with Audrey. In February 1920, his wife, Julia Wilkins, was found dead and it turned out that Dr. Walter killed her so that he would be able to marry Munson. Whether she had an affair with the doctor or was in any way involved with him is unknown. When questioned by the police, Audrey denied any romantic relationship with Wilkins, who sentenced to death in the electric chair.

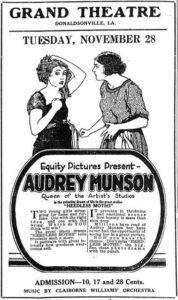

In 1921, Munson appeared in a move Headless Moths, based on her life story. She received a $27,000 check which she claimed to be invalid and for which she filled a suit against the agent-producer, Allan Rock.

Things went downhill for Audrey. No more marriage proposals, no more job proposals, no income, living off the earnings by her mother who sold utensils door to door. In 1922, at the age of 31, she swallowed a solution of mercury bichloride, attempting suicide. In 1931, Munson was committed to St. Lawrence State Hospital for the Insane in Ogdensburg where she remained for 65 years, until her death.

America’s first supermodel had no visitors at the hospital until 1984 when she was found by her half-niece, Darlene Bradley. She died in 1996, at the age of 104.“Long after she and everyone else of this generation shall have become dust, Audrey Munson, who posed for three-fifths of all the statuary of the Panama–Pacific Exposition, will live in the bronzes and canvasses of the art centers of the world.” – New Oxford Item, April 1, 1915