Archaeologist Recently Discovered Oldest handwritten documents in UK Excavated in London dig

Archaeologist Recently Discovered Oldest handwritten documents in UK Excavated in London dig

Tertius the Brewer, Junius the Cooper and Julius Classicus – the up-and-coming military commander who would turn traitor against Rome a decade later – have sprung back to life from the first decade of Roman London, their names – along with the first reference to London itself – miraculously preserved on writing tablets in a sodden hole in the core of the City.

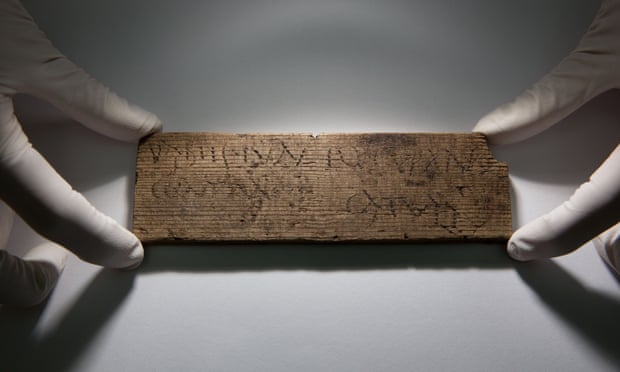

The wooden tablets, preserving the faint signs of the words written on bees wax with a metal stylus almost 2,000 years ago, are the oldest handwritten documents ever found in the United Kingdom.

The tablets were found under a 1950s office block in the still smelly, wet mud of the lost river Walbrook, as the site was being cleared for a colossal new European headquarters for Bloomberg.

“They give us a look into a carpet-bagging community in the new wild west frontier of the Roman empire,” said Roger Tomlin, the expertise on early Roman writing who spent a year poring over the faint scratches on slivers of fir wood recycled from old barrels.

The oldest tablets, one of which was addressed “Londinio Mogontio” – to Mogontius in London – originate from a layer securely dated to the first decade after the Roman invasion in AD43, through the timbers and coins additionally found.

That makes it the earliest reference to the Celtic name the Romans decided for their new settlement, composed half a century before the Roman historian Tacitus used the name in his annals.

Another tablet, the earliest legal document and the earliest carrying a date from Roman Britain, was written on 8 January AD57, when Tibullus wrote promising to repay Gratus – 2 men described as freed slaves – 105 denarii, half a year’s pay for a Roman legionary, for goods delivered.

In total there were 405 writing tablets, 87 of which Tomlin prevailing in deciphering – a process he depicted as “code-breaking”.

“They represent the first generation of Londoners speaking to us,” said Sophie Jackson, the executive of the Museum of London Archaeology unit which excavated the site. She called the tablets “the email of the Roman world”.

A portion of Tomlin’s carpetbaggers got rich quick. Tertius the brewer is almost certainly Domitius Tertius Bracearius, who likewise known from a writing tablet found at Carlisle – and so by about AD85 had a business extending the length of the new Roman territory. Only the outer flap of the tablet survives, addressed to him.

It was a dynamic network. Another tablet records an order of 20 loads of provisions to be delivered from Verulamium – present day St Albans – to London, within a few years of the Boudiccan revolt, in which both settlements had been wrecked.

Another is addressed to “Junius the cooper opposite the house of Catullus”, whose barrels may have been broken up to shave down into more tablets. The tablets initially came in pairs bound together, with a shallow recess filled with beeswax blackened with lampblack.

The letters were scratched into the wax with a sharp stylus and, however the wax had dissolved over the centuries, the words have been deciphered from the faint scratches in the underlying wood.

Only 19 legible tablets had previously been found across London. The new treasury incorporates the names of nearly 100 Peoples, and the tablets include legitimate and business documents, bills and promissory notes, and someone practising the alphabet and numerals – maybe the evidence of the earliest Roman school.

The oldest are less chatty, but earlier than the cache of tablet found at Vindolanda near Hadrian’s wall, which includes requests for warm socks for frozen soldiers serving on the northern frontier.

Tomlin was surprised to find the earliest use of the phrase “per panem et salem”, by bread and salt, recorded as a proverb reflecting on the simple life of the virtuous ancient by Pliny.

The letter asks the beneficiary “by bread and salt” to send 36 denarii, which Tomlin interprets as “you have had your free lunch, now I need some money from you”.

Another name known from the history is Classicus, “prefect of the 6th Cohort of Nervii”, commander in the AD60s of an auxiliary infantry accomplice, probably through the impact of his cousin, Julius Classicianus, who was an official in Britain in AD 61-65.

In AD 70 Classicus, by then in charge of a cavalry regiment on the Rhine, would join the rebellion against Rome in the power struggle after the demise of Nero: his ultimate fate is unknown.

Most of the tablet were imported in rubbish, including stable sweepings, from over the settlements as the Romans brought in tonnes of landfill to build up the sodden river banks and make building stages.

But, some were found within the foundations of a little square timber room, which Jackson portrayed as “the oldest office in England” and probably since the tablets were legal documents, the oldest law centre too.

The site was known to have produced amazing finds when the office block was built among the postwar bomb sites in the 1950s, including the sanctuary of Mithras, which Londoners queued around the square to see in 1954. As part of the current project, its remaining parts are being relocated to its original site.

The archaeologists dreaded there may be little more to find, as so much would have been destroyed by the deep cellars of the office block. Instead, finds poured out from the one little stretch of the Walbrook that had been preserved undisturbed by chance.

The tablets are still being worked on by the researchers, but a selection will go on display – with 100s of other artefacts from the site – when the Bloomberg building opens in 2017.