Archaeologists Find Viking Sword in Central Norway

Archaeologists Find Viking Sword in Central Norway

Swords were not only deadly weapons for Viking warriors but symbols of power. In southern Norway a rare example with gold details and a mysterious inscription was discovered.

Experts believe that the elaborate weapon may belong to one of the hand-picked men of King Canute who fought with King Ethelred of England. The sword was found in the village of Langeid in 2011 but not yet on display. It dates back to the late Viking age and is embellished by gold, inscriptions and other designs.

Its length is 37 inches (94 cm) and the handle is well preserved. The use of precious materials is believed to have belonged to the wealthy man because of the use of precious materials. Archaeologists from the Museum of Cultural History in Oslo University pulled the weapon from a grave in Viking burial ground.

‘Even before we began the excavation of this grave, I realised it was something quite special,’ excavation leader Camilla Cecilie Wenn said. ‘The grave was so big and looked different from the other 20 graves in the burial ground.’

She found post holes in the four corners of the grave, suggesting there would once have been a roof over it – a sign that the grave had a prominent place in the burial ground. At first, they only found two small fragments of silver coins, including a penny minted under Ethelred II in England dating from the period 978-1016.

‘But when we went on digging outside the coffin, our eyes really popped,’ Dr Wenn said. ‘Along both sides, something metal appeared, but it was hard to see what it was. Suddenly a lump of earth fell to one side so that the object became clearer.

‘Our pulses raced when we realised it was the hilt of a sword. ‘And on the other side of the coffin, the metal turned out to be a big battle-axe. ‘Although the weapons were covered in rust when we found them, we realised straight away that they were special and unusual.’

By dating charcoal from one of the post holes, they have shown the grave was dug in around the year 1030, at the end of the Viking Age, which fits with the discovery of the coin too. While the iron blade has rusted, the sword’s handle is well preserved.

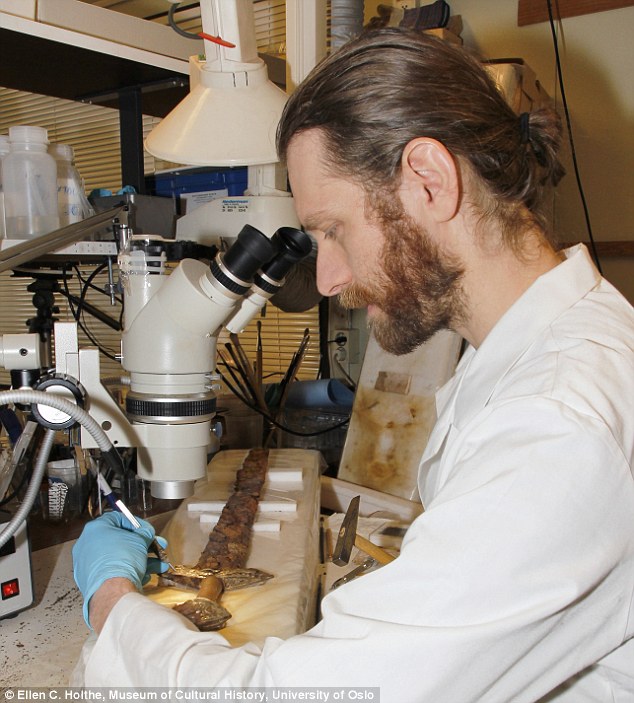

Project leader Zanette Glørstad, said: ‘It is wrapped with silver thread and the hilt and pommel at the top are covered in silver with details in gold, edged with a copper alloy thread.’ Curator Vegard Vike added: ‘When we examined the sword more closely, we also found remnants of wood and leather on the blade.

‘They must be remains from a sheath to put the sword in.’ The sword is decorated with large spirals, various combinations of letters and cross-like ornaments. The letters are probably Latin, but their meaning remains a mystery.’

Dr Wenn said: ‘At the top of the pommel, we can also clearly see a picture of a hand holding a cross. ‘That’s unique and we don’t know of any similar findings on other swords from the Viking Age. ‘Both the hand and the letters indicate that the sword was deliberately decorated with Christian symbolism.’

The experts are unsure how such a sword ended up in a pagan burial ground. ‘The design of the sword, the symbols and the precious metal used all make it perfectly clear that this was a magnificent treasure, probably produced abroad and brought back to Norway by a very prominent man,’ she added.

In Norse sagas, swords reveals a warrior’s status and his strength. They also hint that gold had a special symbolic value in Norse society, representing power.

The metal is rarely found in artefacts from the Viking period, suggesting it was considered extremely valuable. Hanne Lovise Aannestad, the author of a recent article on ornate swords from the days of the Vikings, said: ‘Based on the descriptions in the literature, we can say that the sword was the male jewellery par excellence of the Viking Age.’

The Viking Age was a time of great social upheaval and because of this, symbolic objects may have played a role in maintaining social positions, the researchers said.

Ms Aannestad added: ‘There is much to suggest that these magnificent swords were such objects, reflecting the status and power of the warrior and his clan.’ In contrast to the ornate sword, the battle axe found in the same grave has no gold decoration.

However, the shaft is coated with brass, which may have flashed like gold on a sunny battlefield. Such a coating is rare in Norway, but similar battle-axes from the same time have been found in the River Thames in London.

There was a long series of battles along the Thames in the late 10th and early 11th centuries when the Danish king Sweyn Forkbeard and his famous son Canute led their armies against the English king in the battle for the English throne.

The men who fought in these battles were picked from all over Scandinavia and it’s possible that the axes either got lost in the Thames or were thrown into the river after victory. There is a possibility that the sword belonged to a Viking from King Canute’s army.

Further down the Setesdal Valley a runic stone was discovered that reads: ‘Arnstein raised this stone in memory of Bjor his son. He found death when Canute ‘went after’ England. God is one.’ The stone was probably erected by a father whose son never came home.

The Old Norse inscription seems to refer to King Canute’s attacks on England in 1013 to 14, while historic documents suggest his closest army came from leading families and had gilded weapons. The experts think the Langeid sword was made outside Norway, having a possible Anglo Saxon origin, and would have been approved by the king.

Together with the brass-coated axe and English coin, the man laid to rest in the grave seems to have had a connection with England. Dr Glørstad said: ‘It’s quite possible that the dead man was one of King Canute’s hand-picked men for the battles with King Ethelred of England.

‘Seen in connection with the runic stone further down the valley, it is tempting to suggest that it is Bjor himself who was brought home and buried here. ‘Another possibility is that his father Arnstein only got his son’s magnificent weapons back and that, precisely for that reason, he decided to erect a runic stone for his son as a substitute for a grave.

‘When Arnstein himself died, his son’s glorious weapons were laid in his grave. ‘The death of his son must have been very tough on an old man.

‘Perhaps their relatives honoured both Arnstein and Bjor by letting Arnstein be buried with the weapons with such a heroic history.’ Interestingly, the runic stone is the oldest in Norway that refers to Christianity and was carved at a point in time when Christianity was about to take root in society.

People may have chosen to include a mixture of pagan ans Christian elements in a funeral and the Langeid grave is one of the last pagan funerals to have been recorded in Norway. The sword is now on display at an exhibition at the Historical Museum in Oslo, called Take it Personally – an exhibition of personal jewellery and adornment over time.