Archaeology: Room found where Roman emperor Hadrian held power breakfasts 1,900 years ago

Archaeology: Room found where Roman emperor Hadrian held power breakfasts 1,900 years ago

A room has been discovered in which the Roman emperor Hadrian and his reportedly long-suffering wife Vibia Sabina arranged elaborate power breakfasts 1,900 years ago.

Archaeologists discovered the scene at the Villa Adriana, a sprawling 200-acre complex in Tivoli that was originally built for the Emperor as a refuge from the hustle and bustle of Rome in about 120 AD.

By the year 128 AD, Hadrian had begun to rule the empire directly from the villa, which would have housed a large court as well as numerous visiting guests and bureaucrats.

An avid scholar of art and history, Hadrian played a key role in the design of the complex, with buildings named for and reflecting the styles of places he had once visited on his travels.

It therefore merged both Roman and ancient Greek architecture, and was similarly decorated with Greek figures, such as copies of the Caryatids seen at the Acropolis and statues known as Poikilos.

It even had an Egyptian-themed area — Canopus, named for the city in which Hadrian’s lover, Antinous, drowned — with a long, rectangular reflecting pool to represent the Nile in which the young man met his end.

Each of the carefully crafted rooms and structures would have established the Emperor’s taste and power — reinforcing his status among his watching courtiers.

Lying some 20 miles to the east of Rome, at the foot of the Apennine mountains, the Villa Adriana would have been surrounded by landscaped gardens, wilderness areas and cultivated farmlands.

Experts believe that Hadrian would begin his days at the villa by taking breakfast on a marble platform in a flooded, semi circular room.

Two fountains would have spurted water into the air behind him and his wife, Vibia Sabina, while light poured in through a vast window, casting imposing silhouettes of the pair to those so favoured to be allowed to see them.

‘It was a quasi-theatrical spectacle,’ Villa Adriana director and Italian art historian Andrea Bruciati told the Times when the site was reopened yesterday.

According to the expert, the platform would have connected to four bedchambers, each with a latrine bedecked with marble panels and precious stones.

‘The villa was a machine that served to represent the emperor’s divinity. It was almost futuristic,’ Dr Bruciati continued.

‘Politicians could learn from him today,’ he concluded.

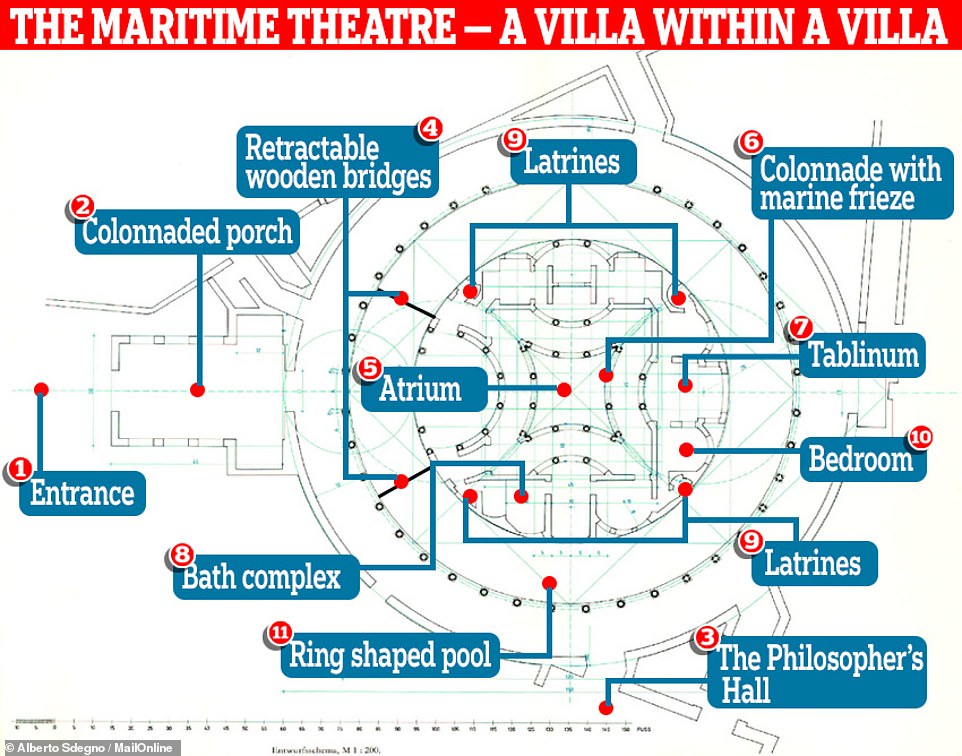

Arguably the grandest part of the villa was the so-called Maritime Theatre, a 35-room complex isolated from the rest of the complex by a marble-lined, ring-shaped pool which, in turn, was surrounded my a colonnade paved in white mosaics.

This setting may be familiar to British TV afficidionas as the location of the stand-off between Sandra Oh’s ‘Eve Polastri’ and Jodie Comer’s fashionable assassin Villanelle in the second season of the BBC series ‘Killing Eve’.

Thought accessible by means of two retractable wooden bridges, the 130-feet wide island enclosure would have been used by Hadrian as a sort-of retreat — a ‘villa within a villa’ — with a design partly inspired the layout of a typical Roman home.

Its centre would have featured a rainwater catching basin known as an ‘impluvium’, around which were nestled a lounge, a library, heated baths, various bedrooms with attached latrines, a library.

In the present day, access to the central island in the theatre is granted to tourists visiting the site by two permanent concrete bridges.

After Hadrian’s passing in the July of 138 AD, the Villa Adriana went on to be occupied by some of his successors — including, it is believed, his adopted son Antoninus Pius, Marcus Aurelius and Septimius Severus.

In the 270s, the site is thought to have become the home of Septimia Zenobia, the deposed queen of Syria’s Palmyrene Empire. By the 4th century AD and the decline of the Roman empire, however, the villa fell into disuse, with valuable marble and statues having been removed.

The complex would go on to be used as a warehouse by both sides during the war between the Ostrogoths and the Byzantine Empire, with marble from the structure being repurposed to extract lime for construction using on-site kilns. Much of the remaining marble was later removed in the 16th century to decorate the nearby Villa d’Este.

Today, the ruined villa is protected as a UNESCO World Heritage site — and, in September 2013, a network of tunnels beneath the site, which were thought to have been used as service routes for staff to move around the complex while remaining out of sight.