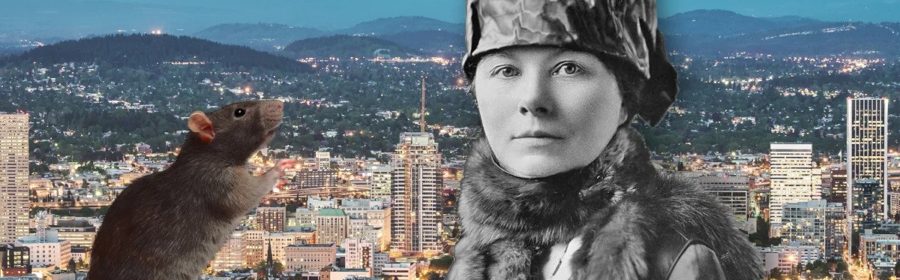

How one Woman Single-Handedly Saved Portland from the Plague in 1907

How one Woman Single-Handedly Saved Portland from the Plague in 1907

At the time of summer 1907, Esther Pohl was a well-known sight around Portland, Oregon. Thirty-five years out of date, with wavy hair piled to the top of her head, she was recognized for cycling from home to visit the patients of her personal obstetrics follow.

She had also worked at the metropolis well-being council since 1905 one of the first ladies in Oregon to follow medication. However, on July 11, 1907, when the well-being board unanimously elected her Portland’s well-being commissioner, she attached a brand-new feather to her cap. This made her the first lady to be an officer in a major American metropolis.

Pohl began her time to fight the widespread infectious diseases of the early twentieth century — maladies such as smallpox, whooping cough, and tuberculosis, known to her as “the greatest evil of this day.”

In addition to one of the busiest ladies in the region, the Oregon Journal, referred to as “one of the best-known woman physicians on the coast.”

But earlier than the summer time of 1907 was via, she’d confront an much more formidable foe: the bubonic plague. Armed with the newest scientific data and decided to not repeat the errors of different cities on the Pacific, Pohl marshalled a response that targeted on the actual enemy driving the plague’s unfold: rats—and their fleas.

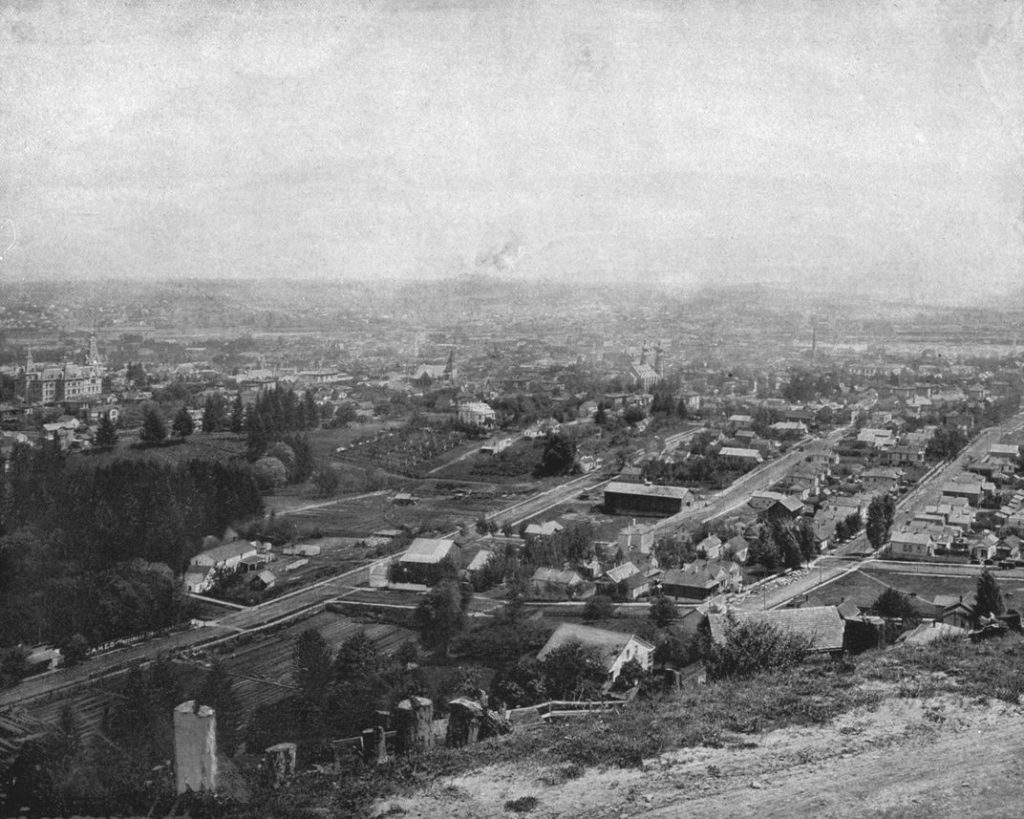

Most well-known as a medieval scourge that killed tens of millions throughout Asia, Europe and Africa in the mid-14th century, the bubonic plague was by no means totally eradicated from the globe (in actual fact, it’s nonetheless round). The 1907 outbreak that threatened Portland—a metropolis that will develop to over 200,000 individuals by 1910, making it the fourth-largest metropolis on the West Coast—could be traced again to a wave that started in China in the 19th century after which unfold alongside transport routes. The illness first made landfall on U.S. territory in Hawaii as the century turned. In Honolulu, a number of Chinese immigrants died of the plague in 1899. Reaction from native officers was swift: All 10,000 residents of the metropolis’s Chinatown had been positioned below quarantine in an eight-block space surrounded by armed guards. When the illness unfold to a white teenager outdoors the quarantine zone, officers started burning buildings in a determined try to quell the illness. The subsequent January, a stray spark ignited an 18-day blaze that burned down the metropolis’s whole Chinatown. The devastation was brutal, however it additionally stopped the plague—not less than in Honolulu.

In March 1900, the proprietor of a lumber yard named Chick Gin died in a flophouse basement in San Francisco’s Chinatown. Health examiners known as to his emaciated physique instantly suspected the plague after noticing that his corpse confirmed swelling in the groin space—a tell-tale signal of the illness (“bubonic” comes from the Greek for groin, boubon). The authorities didn’t even wait till the outcomes had been again from the lab to impose a quarantine on Chinatown, trapping about 25,000 individuals in a 15-block space surrounded by rope. No meals was allowed in, and no people set free.

Well-off white San Franciscans had been enraged at the disturbance of their every day lives, since a lot of the metropolis relied on Chinese staff to cook dinner and clear. Yet many comforted themselves with the concept that they weren’t prone to contract the illness themselves. At the time, the plague was usually racialized, as if one thing in the our bodies of immigrant communities—significantly Asian communities—made them extra inclined. It was thought that the plague may solely thrive in heat locales, and amongst those that ate rice as an alternative of meat, since their our bodies supposedly lacked ample protein to fend off the illness.

City and state officers did their finest to stage a cover-up in San Francisco, denying the plague’s presence. As historian of drugs Tilli Tansey writes for Nature, “California governor Henry Gage—mindful of his state’s annual $25-million fruit harvest and concerned other states would suspect a problem—disparaged ‘the plague fake’ in a letter to U.S. secretary of state John Hay and issued threats to anyone publishing on it.” It took an impartial scientific inquiry and at last a concerted disinfection marketing campaign earlier than San Francisco was thought of secure once more in 1904. Meanwhile, 122 individuals had died.

But the plague wasn’t actually gone from San Francisco—removed from it. On May 27, 1907, the metropolis recorded one other plague loss of life. This time, nonetheless, two key issues had been totally different. For one, consultants lastly had a deal with on how the illness was unfolded: in the guts of fleas carried on rats and different rodents. Although the microorganism that causes the bubonic plague, Yersinia pestis, had been recognized again in 1894, at that time scientists had been nonetheless unclear on the way it was unfolding. At the flip of the century, many believed the bubonic plague was airborne and simply unfold from human to human. (Pneumonic plague is unfolded by droplets, however, it’s much less widespread than the bubonic kind.) Scientists had lengthy famous that mass die-offs amongst rats coincided with outbreaks of the plague amongst people, however, the transmission route wasn’t clear. In 1898, Paul-Louis Simond, a French researcher despatched by the Pasteur Institute to the South Asian metropolis of Karachi, demonstrated that contaminated rat fleas may transmit the plague microorganism, however it took a number of years and affirmation from different researchers earlier than the concept was well-accepted.

“For most of human history, no city had a chance against plague, because they thought its cause was miasma, or sin, or foreigners,” writes Merilee Karr, who coated Pohl’s efforts in opposition to the plague for Portland Monthly. “The realization dawned that rats were involved sometime in the eighteenth or nineteenth century. Acting on partial knowledge was dangerous because just killing rats would have sent fleas hopping off dead rats to look for new hosts.”

Another factor that was totally different by 1907: Because public officers now understood how the illness unfolded, they had been prepared to work collectively to stop its transmission. The plague was now not thought of an issue that may very well be confined to a single location: As a port on the Pacific, Portland was susceptible to the similar flea-infested rats scurrying via the harbour and alleys of San Francisco, to not point out Honolulu or Hong Kong. Although San Francisco lagged as soon as once more in mounting an efficient response, by August 1907, U.S. public well-being officers had been urging anti-plague measures up and down the West Coast, together with an order for all vessels in the area to be fumigated and all rats in the ports exterminated.

Esther Pohl went even additional. She designed an anti-plague technique that mixed her scientific and technical experience with an understanding of the energy of the press. One of her first large strikes, in line with Kimberly Jensen—creator of Oregon’s Doctor to the World: Esther Pohl Lovejoy and a Life in Activism—was to ask reporters and photographers alongside on her inspection of waterfront. On September 1, 1907, the Oregon Journal revealed a Sunday exposé headlined “Menace to City’s Health,” describing a horrified Pohl discovering piles of rotting rubbish, uncooked sewage, and a bunch of “unlovely smells” alongside the docks. One specific eyesore at the foot of Jefferson Street was used “as a dumping ground and boneyard for all the dilapidated pushcarts and peddler’s wagons confiscated by police. For half a block there is a wild tangle of milk carts … old rusty iron stoves … worn-out wire cables and rotten woodpiles.” The acres of jumbled, damaged trash had been an ideal breeding floor for rats, to not point out different well being points.

A couple of days later, Pohl reported on the “indescribably filthy” circumstances she discovered to the metropolis’s board of well being, calling for property homeowners—and the metropolis—to be compelled to wash up their messes. The board was supportive, and on September 11, she made a presentation to the metropolis council. She reminded leaders of a spinal meningitis outbreak only a few months earlier than earlier and warned, “Now we are threatened with a much more dreadful disease.” The measures she beneficial had been multi-pronged: Garbage needed to be correctly coated; meals needed to be protected; and rat catchers needed to be employed. Pohl requested for $1,000 to fund the work, with the chance extra can be wanted. The metropolis council permitted her request—and let her know that if she wanted it, they’d give her 5 instances that sum of money.

“She was a compelling speaker,” says Jensen. “Pohl and women’s groups used the media effectively by contacting journalists and photographers to document conditions on the waterfront and other areas to raise public awareness and calls for city action. And business owners were particularly concerned about their bottom line and so the council, aligned with the business, voted [for] the money.”

Pohl additionally resisted calls to racialize the plague, even whereas different native medical consultants endured in drawing a connection between ethnicity and the illness. In December 1907, Oregon state bacteriologist Ralph Matson instructed the Journal, “If we cannot compel the Hindu, Chinamen and others to live up to our ideals of cleanliness, and if they persist in congregating in hovels and hoarding together like animals … the strictest kind of exclusion would not be too severe a remedy.” The paper performed up to his quotes, describing West Coast Chinatowns as “filled with dirt and offal, unsanitary, honeycombed with dark cellars and dark passageways.”

But Pohl by no means singled out Chinatown, or another residential neighbourhood. Portland’s Chinatown, which started to take root in the 1850s, was already below stress because of federal exclusion acts and racist violence, with numbers declining from a peak of about 10,000 individuals in 1900 to someplace round 7,000 in 1910. Pohl averted racist rhetoric and focused the waterfront as an alternative, urging each member of the metropolis’s populace to be vigilant.

In mid-September, Pohl met with Portland enterprise leaders, emphasizing the significance of a clear and vermin-free waterfront. They agreed and fashioned a committee to go and compel enterprise homeowners to wash up. C.W. Hodson, the president of the native commerce membership, defined to the Journal, “There isn’t any plague here now and we are hoping that there isn’t going to be any—but there must be something done besides hoping.” According to the Journal, most of the retailers on the waterfront had been prepared to adjust to the membership’s orders, having already examined the harmful circumstances in the paper.

By mid-September, Pohl is additionally known as in outdoors assist: a rat catcher named Aaron Zaik, who had educated in the Black Sea port of Odesa and likewise laboured in New York City and Seattle. The Oregonian emphasised his use of recent strategies and chemical compounds, in addition to his mastery over “the psychology and habits of the rodent tribe.” Pohl made him a particular deputy on the well being board and was so happy along with his work that after just a few weeks she provided his providers without spending a dime to any property holder.

By the finish of October, Pohl added a brand new prong to the metropolis’s rat campaign: a bounty. She provided Portlanders 5 cents per rat, introduced useless or alive to the metropolis crematory, and instructed them in cautious dealing with so the fleas can be killed alongside the rats. Pohl emphasised that killing rats were a civic responsibility, telling the Oregonian that “everyone in the city, rich and poor, should consider it his duty to exterminate rats.”

By December, Jensen writes, “the plague scare was basically over, and Portland

had had no reported circumstances of the illness.” The co-operation amongst enterprise, the metropolis council and Pohl was outstanding for quite a few causes, not least the undeniable fact that a lot of the orders had been handed down by a 35-year-old lady at a time when Oregon ladies didn’t even have the rights to vote. And whereas a number of causes factored in, Jensen says that Pohl’s work was key: “Her leadership and her skilled use of publicity made her a touchstone for many people to take action.”

In the finish, Portland was the solely West Coast port metropolis that didn’t have any plague circumstances in 1907. Karr says through e-mail, “There has still never been a case of bubonic plague within 100 miles of Portland.” She credits the metropolis’s activated inhabitants, “Esther Pohl’s leadership, and Portland’s willingness to follow her to save their city and their own lives.”

Subscribe to our newsletter!