How Scientists Resolved the Mystery of the Devil’s Corkscrews

How Scientists Resolved the Mystery of the Devil’s Corkscrews

Devil’s corkscrew is one of America’s strangest and most mysterious land formations. Fossils come in all sorts of shapes and sizes. Sometimes it’s fairly simple to figure out what sort of organism a fossil is from, other times, it’s less clear.

The weathering of the native sandstone reveals so often fossiled formations, known as Devil’s Corkscrews, in northwest Nebraska, and in parts of Wyoming which are close to it. The structures, up to seven feet high, can be quite large and are spiral infills. At the bottom, deep end of the spirals, slightly angled tunnels branch off to the side.

The sandstone of the Harrison Formation, which most often includes these structures, is finely grained and dates back to the 20-23 million-year-old Miocene Period.

As Smithsonian reported the origin of these unusual fossils has been the subject of some debate since they were first found in the 19th century by a paleontologist called Erwin Barbour.

Barbour was known for building a collection of fossils for Lincoln University of Nebraska, which was a concerted effort to document all the mammals that used to live in the area. Nothing like these structures existed before Barbour’s discovery in the fossil record.

Daemonelix burrows, or the Devil’s Corkscrew, Miocene of Nebraska, USA (original vintage photo owned by the University of Nebraska; provided here for geoscience education purposes, courtesy of Agate Fossil Beds National Monument).

Barbour was baffled by the formations, and first, he thought they might be the remains of giant freshwater sponges. After he discovered plant material in the fossils, however, he changed his opinion and determined that the fossils had to be from a plant, or perhaps the root system of a plant.

A year later, another paleontologist, Edward Drinker Cope, declared that the fossils were obviously the casts of burrows which were made by some type of large rodent. Cope’s idea was supported by Austrian expert Theodor Fuchs, who further opined that the burrows were probably made by an ancient ancestor of a type of gopher. Barbour hotly contested those ideas, saying it was likely that the area had once been a lake, so it was highly unlikely any rodents had been burrowing in it.

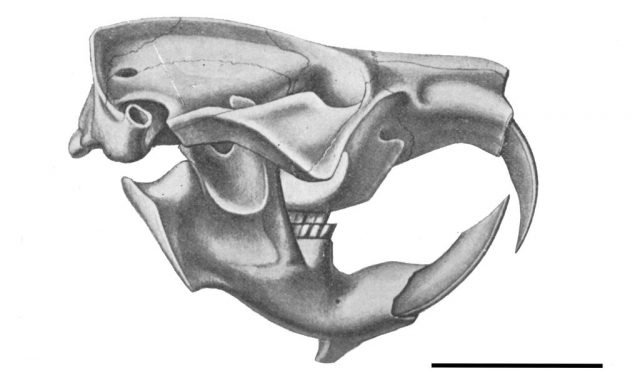

Yet another American paleontologist, Olaf Peterson, obtained several specimens of Devil’s Corkscrew for the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh. He observed that the fossils often seemed to contain the remains of a particular species of ancient beaver called a Palaeocastor, which is known to be about the same size as a prairie dog. As a result of his observations, he supported Cope’s theory over Barbour’s. Fuchs and others on the burrow side of the debate also cited marks found inside the fossils as evidence of claws and used it to support their idea.

Despite how relatively contentious the issue remained at the time, eventually, the burrow theory was generally considered the most likely, and experts stopped doing research on the subject without ever finding conclusive proof.

The issue remained in limbo until the late 1970s, when Larry Martin, a fossil expert from the University of Kansas, and one of his students began studying the unusual fossils. Their work proved instrumental in coming to an understanding of what the fossils actually represented.

When they began their work, scientists had already rejected the idea that the area around the Harrison Formation was once a lake, and determined that the sandstone was not the result of sediment in water, but was instead the accumulation of wind-borne debris that had blown in during year after year of the type of dry conditions that is still prevalent in the area today.

Martin and his student, Deb Bennett, learned that the incisors of the now-extinct beaver suggested by Olaf Peterson were a match for the interior grooves found in many of the fossils. The spirals were, in fact, burrows made by the beavers who dug them out using left- and right-handed strokes of their teeth.

Martin and Bennett found that the incisor teeth of the extinct beaver Palaeocastor were a perfect match for the grooves on the infillings of the Devil’s Corkscrews. (Olaf Peterson’s 1906 study)

While the beavers also left claw marks, these were usually found on the bottom and sides of the ‘tunnels.’ The beavers would first dig down in the tight spiral, but would then start to go up again at a thirty-degree angle, where they would dig a den for themselves, forming the side tunnel off the bottom of the spiral formations.

Martin and Bennet concluded that the first spiralling descent was a way to maintain humidity and temperature control in their dens. As far as the plant matter that Barbour found, the most likely explanation is that the roots of plants, like the beavers, sought out more moisture, and sent their roots into the borrows to take advantage of their humidity-preserving design.

Those roots would become so abundant due to the more favourable growing conditions that the beavers would have to clear them back every so often. The rock of the Harrison Formation contains a lot of volcanic ash in its sandstone. As a result, rain working its way through the ground over millennia would pick up a lot of silica from it, which is easily absorbed by the plant roots.