India’s Living Root Bridges Could Be The Future of Green Design

India’s Living Root Bridges Could Be The Future of Green Design

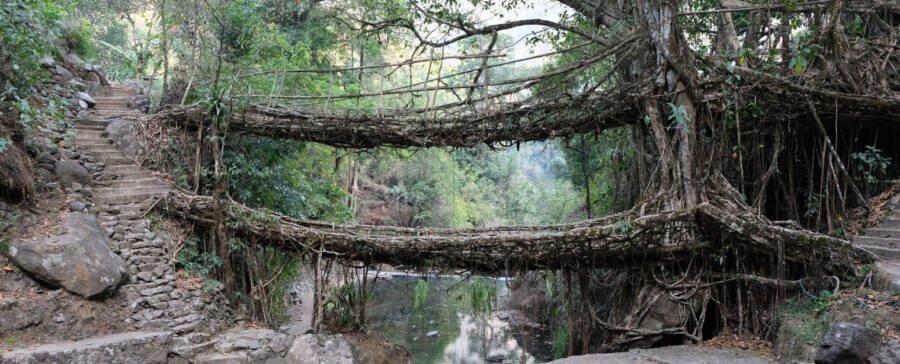

Meghalaya, Indian bridges are about 164 feet long and can carry dozens of people at a time.

Imagine a bridge that actually grows stronger over time. A structure that is part of the environment rather than being imposed on it. These are the living root bridges of India, and they might help in our current global climate crisis.

Living root bridges are river crossings made from some trees ‘ large aerial branches. These roots grow around a bamboo frame or other similar organic material. Over time, the roots multiply, thicken, and strengthen.

A 2019 study by German researchers looks deeper than ever before at living tree bridges — aiming to be the next step towards eco-friendly city structures.

Tree root bridges start humbly; on each bank of the river where a crossing is required, a seedling is planted. The most widely used tree is the rubber fig or the ficus elastica. Once the aerial roots of the tree (one that rises above the ground) sprout up, they are wrapped around a frame and directed to the opposite side by hand. They are planted in the ground when they reach the other side of the bank.

Smaller “daughter roots” are sprouting and growing towards both the original plant and the new implantation area. These are bent to form the bridge structure in the same way. For a bridge to become strong enough to support foot traffic, it can take as much as a few decades. But once they are strong enough, they can last hundreds of years.

The practice of growing living bridges is widespread in the Indian state of Meghalaya, though there are a few scattered around southern China and Indonesia as well. They are trained and maintained by local members of the War-Khasi and War-Jaintia tribes.

Diving deeper into the science of how these trees grow and interlock, the German study points out that aerial roots are so strong because of a special kind of adaptive growth; over time, they grow thicker as well as longer. This allows them to support heavy loads.

Their capacity to form a mechanically stable structure is because they form inosculations — small branches that graft together as bark wears away from the friction of the overlap.

Many living root bridges are hundreds of years old. In some villages, the residents still walk bridges that their unknown ancestors built. The longest tree bridge is in India’s Rangthylliang village and is just over 164 feet (50 meters). The most established bridges can hold 35 people at once.

They serve to connect remote villages and allow farmers to access their land more easily. It is an essential part of life in this landscape. Tourists are also drawn to their intricate beauty; the largest ones draw 2,000 people per day.

Tree root bridges withstand all the climate challenges of India’s Meghalaya plateau, which has one of the wettest climates in the world. Not easily swept away by monsoons, they’re also immune to rust, unlike metal bridges.

“Living bridges can thus be considered both a man-made technology and a very specific type of plant cultivation,” explained Thomas Speck, a professor of Botanics at the University of Freiburg in Germany. Speck is also a co-author of the aforementioned scientific study.

Another co-author of the study, Ferdinand Ludwig, is a professor for green technologies in landscape architecture at the Technical University of Munich. He helped map a total of 74 bridges for the project, and noted, “It’s an ongoing process of growth, decay and regrowth, and it’s a very inspiring example of regenerative architecture.”

It’s easy to see how living root bridges can help the environment. After all, planted trees absorb carbon dioxide and emit oxygen, unlike metal bridges or chopped wood. But how else would they benefit us, and how exactly can we implement them into larger cityscapes?

“In architecture, we are placing an object somewhere and then it’s finished. Maybe it lasts 40, 50 years…

This is a completely different understanding,” says Ludwig. There are no finished objects — it’s an ongoing process and way of thinking.”

“The mainstream way of greening buildings is adding plants on top of the built structure. But this would use the tree as the internal part of the structure,” he adds. “You could imagine a street with a treetop canopy without trunks but aerial roots on the houses. You could guide the roots to where the best growing conditions are.”

This would effectively reduce cooling costs in the summer, using less electricity.

There may not always be rivers to cross in the city, but other uses could be skywalks or any other structure requiring a strong support system.

The prospects are encouraging at a time when our environmental prospects are bleak. On Dec. 2, 2019, at the U.N. Climate Change Conference COP25, U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres warned that the “point of no return is no longer over the horizon. It is insight and hurtling toward us.”

Unless carbon dioxide emissions and other greenhouse gases are greatly reduced, temperatures could rise to twice the threshold set in the 2015 Paris Agreement (2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels) by the end of the century.

Others say the year 2050 is the tipping point. The next generation of living root bridges could be grown and functional as soon as the year 2035.

It’s not too late to begin – as long as we begin now.