The 1842 Slave Revolt By African Americans Enslaved Under The Cherokee Nation

The 1842 Slave Revolt By African Americans Enslaved Under The Cherokee Nation

cc

Unfortunately, the rebellion, known later as the Cherokee slave revolt of 1842, has remained but a footnote in American slavery history.

Despite an exemption from Slavic trade by Native Americans in 1730, many Natives had taken ownership of Black slaves by themselves and moved away from their ancestral lands with slaves in tow.

In addition, by 1860, over 4000 black slaves were owned alone by the Cherokee Nation.

The 1842 Slave Revolt

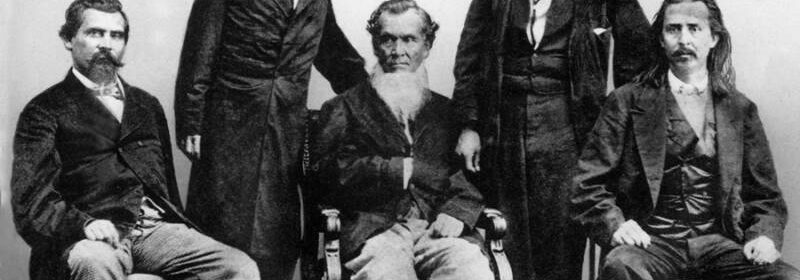

James Vann was born into one of the growing number of Euro-Cherokee trade families that cropped up in the south.

Vann expanded his family’s land to contain several estate holdings by embracing the laws of white settlers. His family’s Cherokee laws would have given more property rights to the women in the family, but by eschewing this, he could keep all the land in his and his son, Joseph’s, name.

Vann also dealt in the slave trade. He owned at least one hundred black slaves and used them to run his plantations.

According to Ties That Bind: The Story of an Afro-Cherokee Family in Slavery and Freedom by Tiya Miles, missionaries who lived near Vann described him as an abusive alcoholic who “terrorized his slaves — burning their cabins, whipping them, and ‘executing’ them ‘in such a horrible way.’”

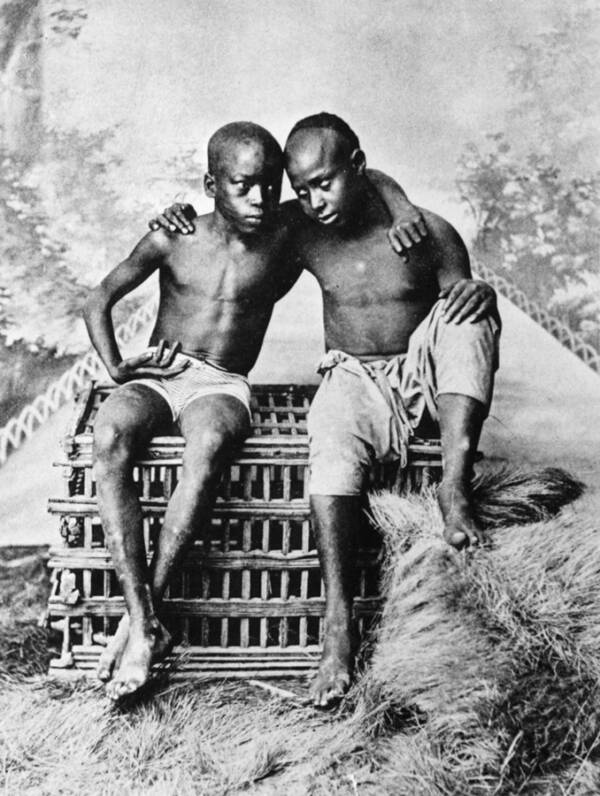

That all came to an end on Nov. 15, 1842, when more than 25 black slaves — the majority from the Vann plantation in Webbers Falls, Oklahoma — revolted. The slaves locked their Cherokee masters in their homes while they slept, stole their guns, horses, food, and ammunition, and ran away.

The runaway slaves headed toward Mexico where slavery was illegal. As they journeyed south, the group crossed into Creek nation territory where they were joined by more escaped slaves of the Creek, raising the group total to about 35 rebels.

Two days after their escape, a Cherokee militia — an 87-man armed force led by Captain John Drew — was deployed to recapture them. The group was eventually caught near the Red River on Nov. 28, 1842.

The slaves were brought to face the Cherokee National Council in Tahlequah and five of them were executed. Cherokee slaveholders blamed the uprising on the influence of the free African Americans living in tribal territory.

The tribe soon passed a law mandating that all free African Americans, except former Cherokee slaves, leave the nation.

Cherokee Freedmen And Their Descendants

A year after the end of the Civil War, the Cherokees — who fought alongside the pro-slavery Confederates — entered into a treaty with the U.S. government that guaranteed tribal citizenship to the tribe’s former slaves. They would be called “Freedmen” and their descendants would be listed on the Dawes Roll, the government’s official tribal registry.

But in 2007, Cherokee members voted to strip 2,800 Cherokee Freedmen of their tribal membership and moved to redefine tribal citizenship as “by blood.” The move sparked a lawsuit that lasted over a decade, ending with a 2019 judge ruling that the descendants of black Cherokee slaves could maintain their citizenship.

“There can be racial justice — but it doesn’t always come easy,” Marilyn Vann, president of the Descendants of Freedmen of the Five Civilized Tribes and a descendant of the Vann family, said of the court ruling.

“What this means for me, is the Freedmen people will be able to continue our citizenship… and also that we’re able to preserve our history. All we ever wanted was the rights promised us, to continue to be enforced.”

As conversations around America’s sordid past of racial inequality expands, the nearly-forgotten history of the black slaves who were owned by the country’s native tribes can no longer be ignored.

The Transatlantic Slave Trade And Native Americans

Even before European colonists brought enslaved Africans to the Americas, slavery was a common practice among the continent’s indigenous tribes, as some nations would take the members of other nations prisoner after their victory in battle.

But slavery, as it was practiced among the natives, was nothing like the transatlantic slave trade later introduced to the continent by 15th-century European settlers in terms of scale.

Indigenous people themselves were pillaged and captured for enslavement by Europeans beginning with Christopher Columbus’ invasion on Hispaniola — where Haiti now stands — in 1492.

Native American children were kidnapped from their tribes and put in abusive reform schools.

As Europeans colonized the Americas, both natives and Africans were put to work on plantations, constructing settlements, and fighting in battles against other native tribes.

Hordes of Native Americans were exported to European colonies in the Caribbean and elsewhere, many of who succumbed to foreign diseases overseas.

If Native American slaves weren’t exported, then they often escaped and found refuge among tribal communities that had remained free.

But the enslavement of Native Americans was outlawed completely in the late 1700s, by which time the African slave trade was well established.

Then, some Native Americans became slave owners too.

The Sordid History Of Native Americans As Slave Owners

Colonists began to force assimilate Native Americans into white culture, which meant that indigenous tribes were expected to adopt the practices of white society — including slave-holding.

There were five tribal nations, in particular, that the white colonists found to be the most agreeable, and they called them the “Five Civilized Tribes.” These were the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Creek, the Seminole, and Choctaw.

In 1791, the Cherokee nation signed the Treaty of Holston which mandated that tribal members adopt a farming-based way of life — another way for white colonists to “civilize” the natives — that would use “implements of husbandry” provided by the government. One such “implement” was slavery.

The promise of land ownership and protection from the U.S. government was enough to incentivize many Native American landowners to uphold the practices of white men. By 1860, the Cherokee nation became the largest slaveholding tribe among all the Native Americans.

Thousands of African Americans lived in the south’s tribal territories, and there were some who lived among the tribes as free people.

The fraught history of Native Americans as both slaves and slave owners continues to spark discussion among historians. Some experts consider the complicity of the “Five Civilized Tribes” in upholding slavery as a means of survival in a world where resources were controlled by white laws.

But to others, that kind of argument exempts Cherokee slaveowners from their persecution of black people.

“In truth, ‘Civilized Tribes’ were not that complicated,” National Museum of the American Indian curator Paul Chaat Smith told Smithsonian Magazine. “They were willful and determined oppressors of blacks they owned, enthusiastic participants in a global economy driven by cotton, and believers in the idea that they were equal to whites and superior to blacks.”

Though records suggest the few Cherokee slaveholders that existed were more liberal and less tyrannical than white slave owners, there are historical exceptions. For instance, half-white half-Cherokee landowner and slaveholder named James Vann, who was known for his money and cruelty.

Subscribe to our newsletter!