The fossil of a bizarre mammal, called ‘crazy beast,’ has been discovered in Madagascar

The fossil of a bizarre mammal, called ‘crazy beast,’ has been discovered in Madagascar

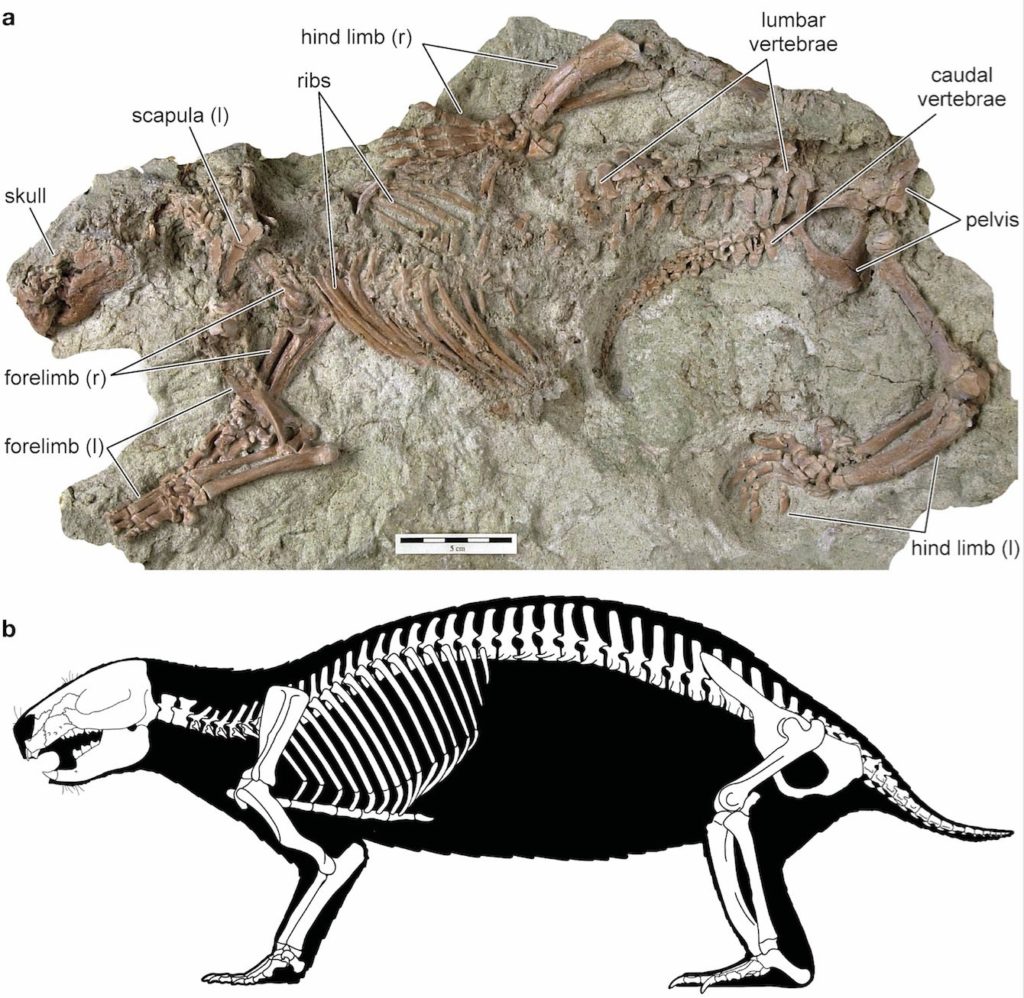

Scientists in Madagascar have discovered a remarkably intact ancient fossil of a bizarre new species of mammals.

The remains are the first near-complete fossil of the badger-esque creature named “Adalatherium hui,” or “crazy beast,” which roamed Gondwana ‘s southern supercontinent 66 million years ago, according to a new study published in Nature journal Wednesday.

But with the results, scientists are still unable to parse the anatomy of the crazy beast, and are not sure how the animal walked.

The creature is also oddly large for a mammal of his time — around 100 times bigger than the mostly rodent-sized mammals of the Mesozoic era.

“Its many uniquely bizarre features defied explanation in terms of relationships to other mammals. In this sense, it was a ‘crazy beast,’” said Denver Museum of Nature and Science paleontologist David Krause, the lead author of the study published.

There are some clues to its behavior. Adalatherium was a plant-eater, with rodent-like teeth to gnaw on roots and other vegetation.

It was probably a skilled digger that could have excavated burrows thanks to its powerful hind legs and long claws on its back feet.

But the creature’s gait has baffled researchers. Its smaller front legs were placed beneath its body like other mammals, but its back legs fan out more akin to a reptile, meaning it likely sauntered like a lizard with its spine swaying side to side.

Gondwana, Earth’s southern supercontinent that included Africa, South America, India, Australia and Antarctica, was full of hazards for crazy beast; it was likely preyed upon by dinosaurs, crocodiles and massive snakes.

The creature belongs to a mysterious mammal group called gondwanatherians that lived for tens of millions of years before dying about 45 million years without any living relatives.

“We suspect some of this bizarreness might be due to evolution in isolation on an island,” said New York Institute of Technology paleontologist and study co-author Simone Hoffmann.

“Figuring out how Adalatherium might have moved or eaten with basically no modern analog is one of the most intriguing parts of this project,” Hoffmann added.