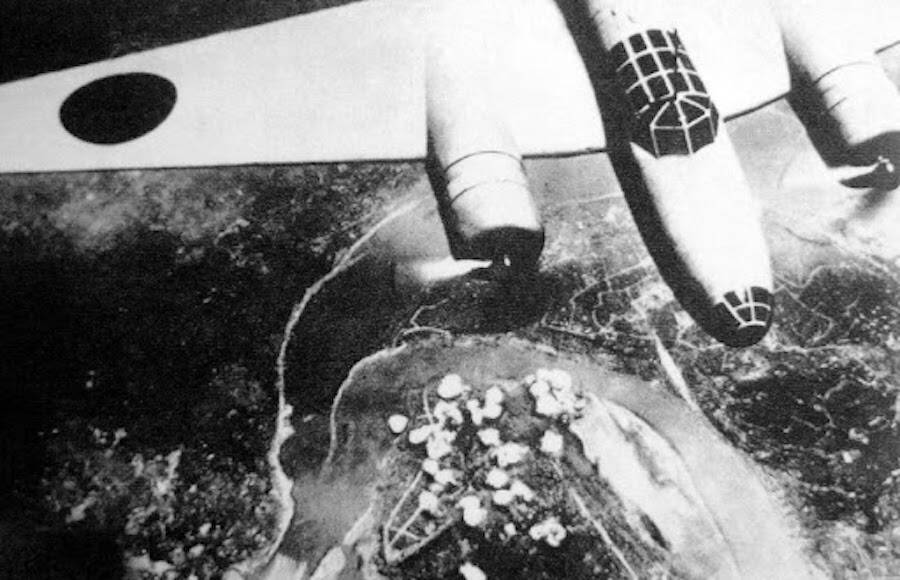

During World War II Japan “bombed” China with fleas infected with Bubonic plague

During World War II Japan “bombed” China with fleas infected with Bubonic plague

The story of World War II has been heard so many times that it can be easily to forget that the general public often does not know some of the most obscure horrors of war.

For example, few know that in the final year of the war, Japan developed a plan for mass death through biological warfare under the title “Operation Cherry Blossoms at Night.”

Japan’s Chemical Warfare Research Unit 731 led by the microbiologist and general Shiro Ishii cames terrifyingly close to crop-dusting the US infected with bubonic plague-infected fleas.

Peppering American landscapes with medieval diseases. Japan has already performed a dress rehearsal against one of its closest neighbours, China, to

In 1949 The court transcripts of the Khabarovsk War Crimes Trials, in which 12 members of the Japanese Kwantung Army were tried as war criminals, revealed as much — and published the chilling details of the war crime:

“The fleas were intended for the purpose of preserving the [plague] germs, of carrying them, and of directly infecting human beings.”

After the Geneva Convention banned germ warfare in 1925, Japanese officials reasoned that such a prohibition only confirmed how potent a weapon it would be. This led to Japan’s biological weapons program in the 1930s and the army’s biological warfare division, Unit 731.

It didn’t take long for the Japanese army to subject Chinese civilians to their cruel experiments. As Japan occupied large swaths of China in the early 1930s, the army settled in Harbin near Manchuria — evicting eight villages there — and built the infamous Harbin facility. What occurred there was some of the most inhumane activity of the 20th century.

The macabre research included locking subjects into chambers and applying pressurized air until their eyes burst from their sockets, or determining how much G-force was required to induce death.

Former Unit 731 medical worker Takeo Wano said he witnessed a man pickled in a six-foot-high glass jar — after being vertically cut into two pieces. There were other jars that contained heads, feet, and even entire bodies, sometimes labeled by the victim’s nationality.

By October 1940, Japanese forces had turned to plague warfare. They bombarded Ningbo in eastern China and Changde in north-central China with infected fleas. Qiu Mingxuan, who survived the bombing as a nine-year-old and later become an epidemiologist, estimated that at least 50,000 citizens were killed due to these bombardments.

“I can still remember the panic among the people,” said Mingxuan. “Everybody kept their doors closed and was afraid to go out. The stores were closed down. The schools were closed down. But by December, the Japanese airplanes came to drop bombs almost every day. We couldn’t keep the quarantine area closed. The people inside ran to the countryside, carrying the plague germs with them.”

On the heels of such a resounding success, Unit 731’s death-dealing concoction was ready to make the long trip across the Pacific.

Japan initially planned to launch large balloon bombs that would ride the jet stream to America. They were successful in delivering around 200 of them. The bombs killed seven Americans, though the U.S. government censored reports of the killings.

Operation Cherry Blossoms at Night would have seen kamikaze pilots strike first against California. The instructor for new Unit 731 recruits, Toshimi Mizobuchi, planned to take 20 of the 500 new troops who arrived in Harbin in 1945 to the southern California coast on a submarine. They would then man an onboard plane and fly it to San Diego.

Thousands of plague-riddled fleas would be deployed as a result, dropped by the troops who would take their own lives by crashing onto American soil.

The operation was set for Sept. 22, 1945. For surviving witness and chief of the attack force, Ishio Obata, the mission was so gut-churning that it was difficult to recall decades later.

“It is such a terrible memory that I don’t want to recall it,” he said. “I don’t want to think about Unit 731. Fifty years have passed since the war. Please let me remain silent.”

Fortunately, the Cherry Blossoms plot never came to fruition.

One Japanese Navy specialist claimed the Navy would have never approved this mission, especially in the latter half of 1945. By that point, protecting Japan’s most valuable islands was far more important than launching attacks on the United States.

By Aug. 9, 1945, the country started blowing up as much evidence of their Unit 731 experimentation as humanly possible. Nonetheless, its history survived — partly due to the United States granting General Shiro Ishii immunity in exchange for his research.

There’s still an open debate on how close Cherry Blossoms at Night was to being executed. What is known is that during a critical meeting in July 1944 it was General Hideki Tōjō who rejected using germ warfare against the United States.

He recognized that Japan’s defeat was most likely imminent and that the use of bioweapons would only escalate America’s retaliation.

Before he died of throat cancer in 1959, Shiro Ishii lived out his life in peace. Many of the men below him in the chain of command were later elevated to higher places of power in Japan’s government. One became Tokyo’s governor, another the head of the Japan Medical Association.

When asked about their actions decades later, many of the men rationalized their wartime research. For the Unit 731 medic who cut one Chinese prisoner into pieces without anesthesia, the logic was all quite simple.

“Vivisection should be done under normal circumstances,” he said. “If we’d used anesthesia, that might have affected the body organs and blood vessels that we were examining. So we couldn’t have used anesthetic.”

When asked how these experiments could have possibly included children, he was just as blunt.

“Of course there were experiments on children,” he said. “But probably their fathers were spies. There’s a possibility this could happen again. Because in a war, you have to win.”

Similar reasoning could have seen Operation Cherry Blossoms at Night brought to its full completion. Ultimately, it may have only been Hideki Tōjō’s intervention that prevented the mass death of American civilians. But when his turn finally came, no one intervened to save Tōjō.

A little over a week after Japan’s surrender, Tōjō attempted suicide with an American pistol. His life was saved with a transfusion of American blood. Then it was taken three years later, when Hideki Tōjō was hung by an international tribunal for war crimes.

Subscribe to our newsletter!