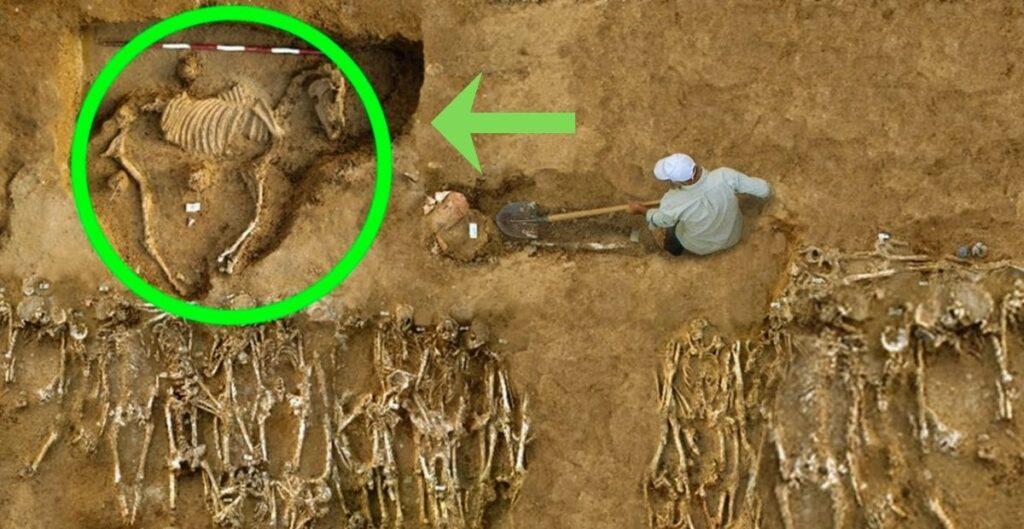

A Horse Skeleton Reveals the Hidden Death of 54 Ancient Soldier Corpses

A Horse Skeleton Reveals the Hidden Death of 54 Ancient Soldier Corpses

Scientific analyses of mass graves believed to be associated with battles fought at Himera, Sicily, between the Greeks and Carthaginians in the 5th century BC have provided new insights into the genetic ancestry of the island’s inhabitants, and also the role of warfare in triggering contact between distant cultures.

According to the writings of ancient Greek historians Herodotus and Diodorus Siculus, two major battles occurred during the 5th century BC in which Phoenicians from North African Carthage attacked the ancient Greek city-state (polis) of Himera, on the north coast of Sicily.

Himera successfully defended itself in the first battle of 480 BC through an alliance with neighbouring Greek Sicilian poleis Syracuse and Agrigento but was later defeated and destroyed in the battle of 409 BC, in which Syracusan soldiers, initially sent to aid Himera, turned back to defend their polis.

Now, a new study, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, has shed light on the life histories of those involved in the Battles of Himera.

As part of the study, led by an international team of researchers from the Universities of Harvard, Florence, Vienna, Northern Colorado, and Georgia (Athens), the genomes of 33 individuals excavated from Himera’s West necropolis were analysed.

This sample included 11 individuals from single graves believed to represent civilians, and 22 individuals from mass graves thought to be soldiers involved in the Battles of Himera – an association purported by the fact that they appear to have been young or middle aged at the time of death, with some exhibiting evidence of skeletal trauma, including several examples of arrowheads lodged in bone.

A further 21 individuals were analysed from two nearby settlements associated with the indigenous Sicani culture.

Geneticist Dr David Reich of Harvard University explained: ‘While the Sicilians of the 1st millennium BC were largely drawn from the local population descended from the Bronze Age, the inhabitants of Himera not only have Aegean and local Sicilian ancestry, but also come from much further afield.’

The genomic analysis revealed that all the individuals from the mass graves associated with the battle of 480 BC show genetic affinities with populations from north-eastern Europe, the Caucasus, and the Eurasian steppe (Scythia).

‘Such extreme genetic diversity in a single burial context is unprecedented for this period of classical history,’ added Dr Alissa Mittnik of Harvard University.

The study also found that many of those believed to have died in the 480 BC conflict had strontium and oxygen isotopic signatures outside of Sicily, indicating that they only travelled there as adults.

In contrast, all of those sampled from the mass graves associated with Himera’s defeat in 409 BC were consistent with an indigenous Sicilian or more general Aegean genetic profile. Evidence of a local origin and upbringing was supported by isotopic analysis.

These findings indicate that the combatants involved in the 480 BC conflict had diverse cultural backgrounds, and provide physical evidence that may support interpretations about the involvement of mercenaries which had been employed by the Syracusan army in large numbers.

The genetic homogeneity of those interred in the mass graves associated with the battle of 409 BC also supports accounts that Himera was defeated having been left to fend for itself.

‘It is such a clear example of how genetics and isotopic analysis corroborate and enrich the historical accounts and archaeological evidence,’ said Professor Britney Kyle of the University of Colorado.

Professor Ron Pinhasi of the University of Vienna added that the results ‘shed light on warfare as a mechanism for cultural contact and positions soldiers, particularly mercenaries, as long-distance carriers of ideas, technologies, languages and genes.’