How London Bridge Ended Up In Arizona

How London Bridge Ended Up In Arizona

In 1968, an American tycoon bought London Bridge—all 10,000 tons of it—and moved it brick-by-brick to the desert town of Lake Havasu City, Arizona.

How did London Bridge come to be one of the biggest tourist attractions in Arizona, second only to the Grand Canyon? Was it an error on the part of the purchaser? Or was it a clever way to dispose of a decrepit structure, making way for progress, while making a profit in the bargain?

London Bridge is where London started: the relative narrowness of the River Thames at that point is what led the Romans to found a city on the site in the first place.

Over the centuries, various bridges occupied this site, linking the City to Southwark on the South Bank of the Thames. Each, in turn, was lost – to fire, or storm, or Vikings.

The longest-lived seems to have been the 12th century “Old London Bridge”, whose arches supported not just a road across the Thames, but as many as 200 buildings, of anything up to seven storeys high.

In the early 19th century, the Scottish civil engineer John Rennie won a competition to design a replacement. The new London Bridge was 100 feet west of the previous bridge: 928 feet long, 49 feet wide, and supported by five stone arches, it lasted for over a century.

By the 1960s, though, the city’s population had more than quadrupled, and London Bridge was supporting cars and buses rather than horse-drawn carriages. To make matters worse, it was said to be sinking at the rate of an inch per eight years; although technically not “falling down”, it was still enough to give London’s authorities cause for concern.

In 1967, the Greater London Council had decided that a new bridge would have to be constructed and the old one torn down.

Usually, under the circumstances, abandoned structures would be simply abandoned or destroyed. (Euston Arch, for example, ended up in the River Lea.) But then, Ivan Luckin, a former journalist and PR man serving on the committee working on the scheme, came up with a better idea: why not flog the bridge off to some rich eccentric? Never mind that it was only 130 years old: pitch it right, and you could sell it as an important historical artifact, and improving the state of London’s coffers into the bargain.

This was not as crazy a scheme as it may now sound. Newspaper mogul William Randolph Hearst – whose life inspired Orson Welles’ film Citizen Kane – used to buy old European buildings, then ship them back in piles to be reassembled on his California estate.

After some initial cynicism, Luckin’s colleagues embraced the idea, and the bridge was placed on the market. In order to sell the idea, Luckin himself visited New York to address the British-American Chamber of Commerce.

At around the same time Robert P. McCulloch, a Missouri-born oil and aviation entrepreneur and chainsaw tycoon (!), was facing his own problems. He’d founded Lake Havasu City on 16,000 acres of western Arizona land in 1963.

But the eponymous lake, an arm of the Colorado River which he’d thought would make the new city an attractive resort, was in serious danger of going stagant.

To prevent that, his engineers created a new channel, turning a peninsula into an island. That though created a need for a new bridge. What better way to solve the problem, and to put his new city onto the map, than by buying the historic London Bridge

So in April 1968, McCulloch agreed to pay just under $2.5m for the bridge on April 18, 1968. (He was so keen to get hold of it that, despite the lack of competition, he paid twice the value the London authorities had expected.) He then spent $7m more, to have the granite blocks numbered, dismantled, trimmed to size and lugged across to the US.

The reconstructed bridge, bridging the channel between Thompson Bay and Lake Havasu, opened to the public in 1971.

Some have come to believe that McCulloch had bought the wrong bridge: that he had meant to buy the far more striking Tower Bridge, but was somehow conned into buying London Bridge.

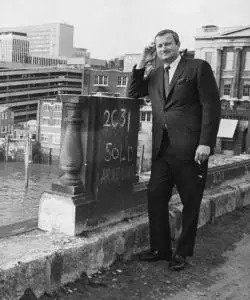

There’s no evidence, though, that this is true – and a fair amount that it isn’t. The chainsaw entrepreneur got himself photographed on the London Bridge, with the Tower Bridge clearly visible behind him. For his part, Luckin always insisted on the honesty of the deal.

So, yes, a rich American did once agree to buy London Bridge – but no, he wasn’t conned. It’s still there, giving its name to a local resort: