Reconstructed Neanderthal chest reveals unusual breathing technique to power muscular bodies in harsh climates

Reconstructed Neanderthal chest reveals unusual breathing technique to power muscular bodies in harsh climates

According to a new revelation, Neanderthals were not hunched-over savages. This may change our perception of man’s evolution dramatically.

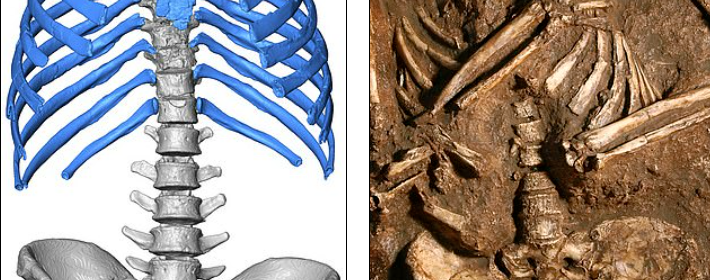

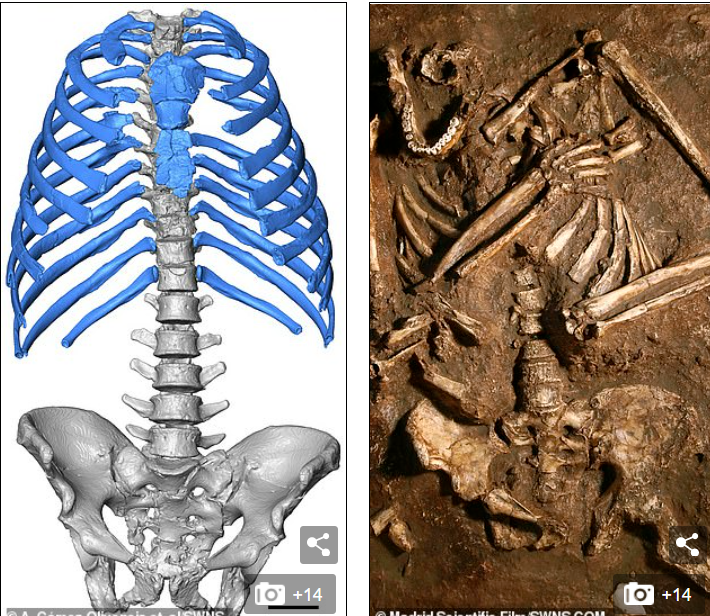

The rib cage of a Neanderthal has been digitally reconstructed, revealing that the ancient hominid had a better stance and stronger lungs than modern humans.

The upright walking style of Neanderthals, far from the knuckle-dragging beasts we imagined them to be, allowed them to walk far further than Homo sapiens.

This discovery has added more backing to the growing consensus that our ancient relatives were far more sophisticated than originally thought. Unlike humans, the ribs connected to the spine in an inward direction – forcing the chest out.

This made them tilt slightly backwards, with little of the forward curvature of the lower or ‘lumbar’ vertebral column that is unique to humans. Anthropologist Dr Markus Bastir, of the National Museum of Natural History, Madrid, said: ‘The differences between a Neanderthal and modern human thorax are striking.’

The thorax includes the rib cage and upper spine which forms a cavity to house the heart and lungs. Lead author Dr Asier Gomez-Olivencia, a palaeontologist the University of the Basque Country, Bilbao, said: ‘The Neanderthal spine is located more inside the thorax, which provides more stability. Also, the thorax is wider in its lower part.’

This shape of the rib cage suggests a larger diaphragm and therefore greater lung capacity.

Senior author Dr Ella Been, of Ono Academic College, Israel, said: ‘The wide lower thorax of Neanderthals and the horizontal orientation of the ribs suggest they relied more on their diaphragm for breathing. ‘Modern humans, on the other hand, rely both on the diaphragm and on the expansion of the rib cage for breathing.’

This would have had a direct impact on their ability to survive on limited resources in the harsh environments they occupied, explained corresponding author Professor Patricia Kramer.

The first reconstruction of a Neanderthal’s ribcage was based on the most complete skeleton unearthed to date. The 60,000-year-old Neanderthal male known as Kebara 2 underwent complex CT scans to create a 3D model of his chest.

The young adult, also known as ‘Moshe’, was found in Kebara Cave in Northern Israel’s Carmel mountain range in 1983 and is complete except for the skull. Using virtual reality and CT scans allowed the team to model the fragile bones in a non-invasive manner that avoids damaging the specimen.

Direct observations of Moshe, currently housed at Tel Aviv University, and medical CT scans of vertebrae, ribs and pelvic bones were combined with specialised 3D software to create the images.

Dr Alon Barash, a lecturer at Bar Ilan University in Israel, said: ‘This was meticulous work. We had to CT scan each vertebra and all of the ribs fragments individually and then reassemble them in 3D.’

They then used a technique called morphometric analysis to compare the images of Neanderthal bones with medical scans of those from present day men.

Debate has lingered over the structure of the thorax, the capacity of the lungs and what conditions Neanderthals could adapt to since their existence was discovered almost 200 years ago.

Lead author Dr Asier Gomez-Olivencia, a palaeontologist the University of the Basque Country, Bilbao, said: ‘The shape of the thorax is key to understanding how Neanderthals moved in their environment because it informs us about their breathing and balance.

‘The Neanderthal spine is located more inside the thorax, which provides more stability. Also, the thorax is wider in its lower part.’

Professor Kramer said the next step is to learn how Neanderthals breathed and for what purposes they might have required powerful lungs. This will tell us more about how they moved and the environment in which they lived.

These physical traits may have made them more or less vulnerable to climate change – the suggested cause of their extinction.

Professor Kramer said reconstructing the thorax was an exercise in starting from scratch, deliberately trying to avoid being influenced by past theories of how Neanderthals looked or lived.

She added: ‘Thinking through all the permutations of the different fragments, it was like a jigsaw without all the pieces. What do the pieces tell us?

‘People have told you it should be a certain way, but you want to make sure you are not over reconstructing, or reconstructing it the way you think it should be. You are trying to maintain a neutral approach.’

The findings back a virtual reconstruction of Moshe’s spine by the same team two years ago that suggested he had an upright posture. Studies in recent years have suggested humans and Neanderthals interbred.

Once depicted as grunting and slouching sub-humans, Neanderthals are now known to have had brains as large as ours and their own distinct culture.

They buried their dead, tended their sick and co-existed with our own ancestors in Europe for thousands of years before becoming extinct just as modern humans flourished and began to spread throughout the continent.