The Herero Genocide: Germany’s First Mass Murder

The Herero Genocide: Germany’s First Mass Murder

While the horrors of the Holocaust are now universally known, there is far less awareness exists of the previous genocide that took place under German auspices, in what was then the German colony of South-West Africa.

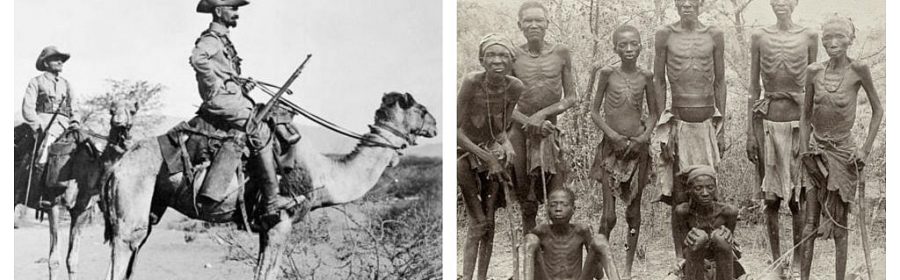

According to scholars, the first genocide in the 20th century, The German forces killed thousands of Nama’s people and Herero between 1904 and 1907 in what is today Namibia.

In many ways, it eerily presaged the Shoah: the use of concentration and death camps; rape; and intentional starvation. These murderous methods are causing one scholar to look at both this genocide and the Holocaust in a new light.

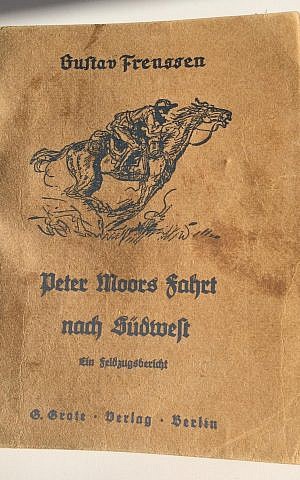

The author Elizabeth Baer makes an unprecedented case that a link can be found between the two genocides by analyzing literary texts. In his book published late last year, “The Genocidal Gaza: From Germany’s South West Africa to the Third Reich.”

The texts span from a diary by Nama revolutionary Henrik Witbooi, who kept a record while battling colonization, to works by German author Uwe Timm, which include a novel about the genocide in Southwest Africa and a memoir about his brother’s death fighting for Hitler in World War II.

Collectively, the texts surveyed reflect what Baer defines in the book as the “genocidal gaze” — “the attitude of German imperialists toward the indigenous people of German Southwest Africa that is then perpetuated by the Nazis.”

A research professor of English at Gustavus Adolphus College in Minnesota, Baer appreciates that the book will be available to an African audience. “The Genocidal Gaze” is co-published by Wayne State University Press in Michigan, and the University of Namibia Press. It will be used as a textbook in an upcoming course at the University of Namibia about modern genocide.

On August 25, Baer will travel to Namibia to speak at a conference and participate in a book launch. “It’s incredibly exciting,” she said.

The book, Baer’s fifth, originated from several sources — a German Studies Association conference, a seminar at the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, and Baer’s travels to both Germany and Africa, including Namibia.

“It seemed nobody knew about [this earlier genocide],” Baer said.

Germany’s colonial-era was relatively brief, lasting for 30 years and ending with its defeat in World War I. But its impact was deadly: The genocide in Southwest Africa killed 80 per cent of the Herero and 50% of the Nama.

“[In] many respects, it seemed a precursor to the Holocaust,” Baer said. “I could see the parallels.”

Roots of evil

The concept of lebensraum, or living space, widely attributed to be a cause of WWII, was actually developed in 1897 by geographer Freidrich Ratzel while the Germans were fighting indigenous resistance in the Southwest African colony they had held since 1885.

Infamous German General Lothar von Trotha defeated the Herero (also called the Ovaherero) in the Battle of Waterberg in 1904, and the Germans campaigned mercilessly toward an endlosung — or final solution — “a way to eradicate indigenous people,” according to Baer.

Von Trotha’s army forced the survivors of Waterberg — tens of thousands of men, women and children — into the Omaheke Desert, dooming them to death from thirst and starvation. They also created konzentrationslager, or concentration camps, although they were not the first to do so. They also founded what Baer calls “the first death camp” and “a prototype for Auschwitz” — Shark Island, where “people were subject to rape, medical experimentation, no shelter, no food, in cages on the beach.”

Several Germans, after returning home, imparted the evil to the next generation — including the colony’s imperial administrator, Heinrich Goring, whose son Hermann Goring became one of Hitler’s most notorious lieutenants.

Dr. Eugen Fischer performed gruesome experiments on indigenous people, sending their severed heads back to Germany; his university students included another future doctor infamous for his experiments — Josef Mengele.

So much of what the Germans did there, the Nazis did subsequently in the methods, the ideology, of the Holocaust

“It’s almost as if — I hesitate to say it — the genocide in Africa was a kind of dress rehearsal,” Baer said. “So much of what the Germans did there, the Nazis did subsequently in the methods, the ideology, of the Holocaust. I’m not saying this caused the Holocaust, but the ideas and methods were used again.”

Path not taken to Holocaust studies

As Baer researched the African genocide, she noticed an omission.

“The books I could get my hands on were all by historians,” she said. “No one had written a book on how war and genocide were refracted in literary texts. I chose it as the focus for my book.”

At the time, Baer was working on another book, “The Golem Redux: From Prague to Post-Holocaust Fiction.”

But “once I got intrigued by what the Germans had done to the Herero and Nama, I kept my antennae up for texts,” she said. “When I finished up work on the Golem book, I knew I wanted to write on genocide next.”

Baer came to Holocaust studies in an unconventional way. Raised Catholic, she grew up in the 1950s, a time of relative lack of interest in the Holocaust, she said.

Later in life, she and her husband travelled to Germany to visit their daughter, who was studying there. The family went to see two sites that were the scenes of tragedy in WWII: Mauthausen and Dachau. It prompted Baer to embark on a self-driven program of Holocaust study that included a three-week immersive experience in Poland and Israel — “Holocaust boot camp,” she called it — run by Warsaw Ghetto survivors Vladka and Ben Meed.

Baer has been teaching about the Holocaust since 1995, saying, “There’s nothing more important I could teach about.”

A literary look at the ‘genocidal gaze’

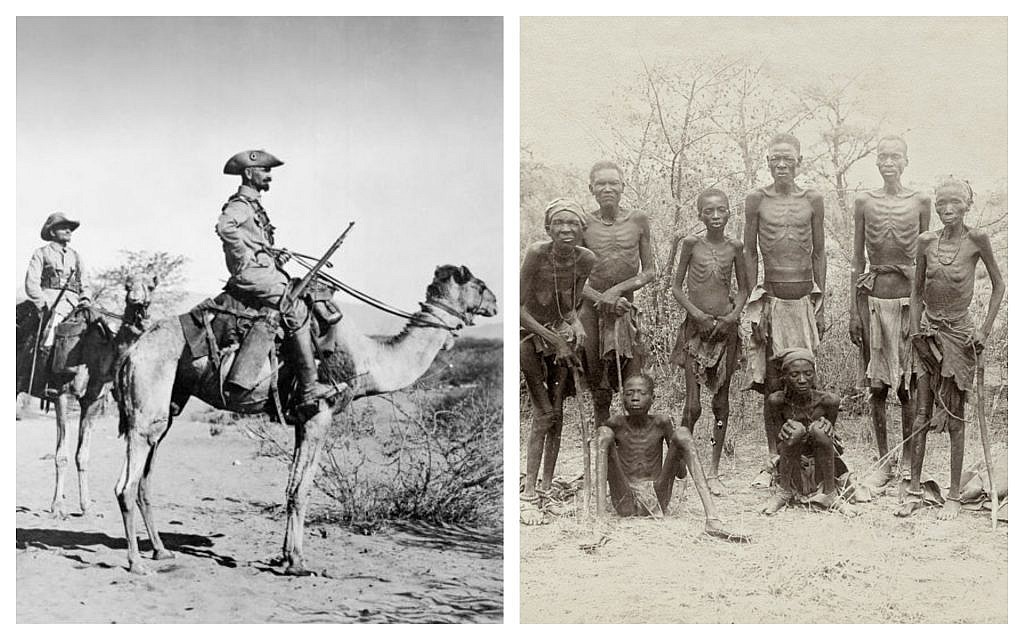

For her latest book, Baer found texts whose creators reflected various perspectives: Witbooi, the Nama revolutionary, who left an archive, and German author Gustav Franssen, whose 1906 novel “Peter Moor’s Journey to Southwest Africa” is described as pro-colonialist by Baer.

Baer also found three post-Holocaust voices: German author Timm, whose books include the novel “Morenga” about the colonial genocide (its title referencing a Nama leader), and the memoir “In My Brother’s Shadow”; South African Jewish artist William Kentridge, whose installation Black Box/Chambre Noire addresses the colonial genocide; and Ghanaian author Ama Ata Aidoo and her novel “Our Sister Killjoy.”

“I try to analyze characters, politics, the use of symbolism, intertextuality, and any paratextual material — photographs, epigraphs, the title chosen, how the cover is designed,” Baer said. “All give us clues about [what the] author’s meaning is, what the author hoped the reader would get from the book.”

For example, Frenssen’s novel “is laudatory of the ideology of the genocidal gaze,” Baer said, describing its argument as follows: “Indigenous people failed to adequately use the land. They were barbaric, uncouth … they did not cultivate, they did not build … They deserved to be killed.”

Published several years after the Battle of Waterberg, Frenssen’s book sold half a million copies. In another link between Southwest Africa and the Holocaust, pocket-sized versions were made for the Wehrmacht to carry in their rucksacks during WWII.

Attitudes changed after the Nazis’ defeat in WWII and what Baer called a “new worldwide awareness of genocide.” She said that “probably the most obvious distinction” in literary works written before and after the Holocaust was their tone.

“I can only imagine [Timm] as a horrified boy, living through the war, losing his brother, [leaving his] father behind in the postwar era,” Baer said.

“In My Brother’s Shadow” shows that Timm “was very opposed to his father’s generation that had gone along with Hitler and fought the war,” she said.

Baer described Timm’s work as reflecting post-Holocaust concepts in Germany such as vergangenheitsbewaltigung, “coming to terms with the past,” as well as vaterliteratur that criticized what Germany — and the new generation’s fathers — had done in the war.

“[After] a decade or so of silence,” Baer said, “kids were old enough to ask, ‘Daddy, what did you do during the war?’”

Other post-Holocaust authors and artists reflected this, Baer said. “It makes sense that Timm’s books, Kittredge’s installation and Ama Ata Aidoo’s novel would all be critical, not praising Germany as Frenssen had done.”

The book does not discuss perhaps the most famous author to address the Southwest African genocide in fiction and link it to the Holocaust — American novelist Thomas Pynchon.

“In Thomas Pynchon’s novel ‘V,’ Southwest Africa is described as setting the stage for Nazism, and in ‘Gravity’s Rainbow’ the Ovaherero resurface in Nazi Germany as the Schwarzkommando who worship a rocket program and are dressed in pieces ‘of old Wehrmacht and SS uniforms,’” University of Michigan professor George Steinmetz wrote in the 2005 scholarly article, “The First Genocide of the 20th Century and its Postcolonial Afterlives: Germany and the Namibian Ovaherero.”

“This is of course entirely fictional, but it does gesture toward the widespread sense of continuity between ‘Southwest Africa’ and Nazism,” Steinmetz wrote.

Pynchon is on Baer’s future reading list, she said. “I have not read Pynchon’s novels on this topic,” Baer said. “They’re so dense, so fanciful. I did not tackle them for the book.”

Little Germany in Africa lingers

Real-life Namibia’s woes did not end once the Germans left and the British and South Africans took over. (Hitler considered reclaiming the former German colonies, Baer said, noting underground German Nazi organizations in Namibia and a strong German presence there in the 1930s and 1940s.) British and South African rule left a legacy of apartheid that the country, independent only since 1990, is still dealing with.

And, Baer said, “Germans in Namibia still own huge tracts of land,” while the coastal city of Swakopmund is “almost a German village. They serve German beer, speak German, act almost like it’s a little Germany.”

But the country overall grapples with poverty — many Namibians “are subsistence farmers with no opportunity for education,” Baer said.

Baer hopes her book will make a difference.

“I feel as if, through my writing, it’s a small contribution to the Namibian people, the remaining remnant of the Nama, Herero and other different ethnic groups in Namibia,” Baer said.