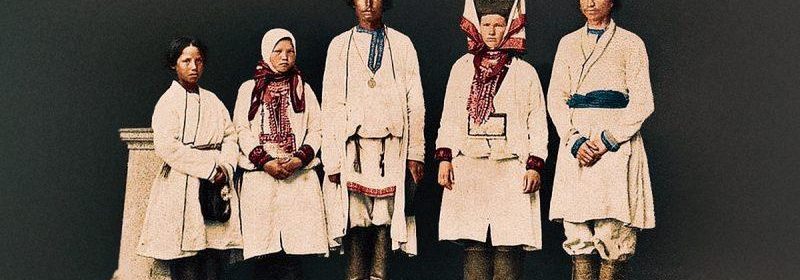

THE MARI PEOPLE – THE LAST PAGANS OF EUROPE

The Mysterious Mari People – Last Pagans of Europe

A Finno-Ugrian population of about 600,000, the Mari are mostly located in the Mari EI Republic, one of the several semi-autonomous ethnic republics of the Russian Federation. Just 15 % of the republic’s population continued to adopt the old belief, and only 45% were Mari (most are ethnic Russians) of the population of around 680,000, which makes the number of practitioners nearly 45,900 in the Mari El Republic.

Using the same arithmetic, it gives us a total of 90,000 mari pagans in total, even though this does not account for the higher level of adherence to their faith of their ancestors found in some of the neighboring republics where many Mari fled in order escape conversion to Christianity.

It’s important to explain what we mean by “pagan” instead of “neopagan” before we get much further. The former has different definitions in different contexts and can be controversial, or even offensive. Originally used to describe polytheists by Roman Christians, in medieval Europe it grew to describe anyone other than a Christian — or in fact, the “right sort” of Christian — including Jews and Muslims, despite their monotheism. Due to this legacy, the Mari reject the word “pagan”.

Pagan means pre-Christian religious practices, and neopagan means a modern beliefs system which accepts the characteristics of authentic ancient pre-Christian beliefs. Despite the changes in the Mari faith over time, there exists a clear unbroken line between adherents in the distant past and in the present.

But rather than being trapped in amber like an ancient insect, the Mari Native Religion (as it is officially registered) has changed enormously.

Living around a bend in the River Volga — Europe’s longest river — the bulk of the Mari were nominally converted to Christianity in the 16th century following the conquest of their lands by Tsar (emperor) Ivan the Terrible as he drove east to bring down the Muslim Kazan Khanate, but the old faith endured as Mari were baptized into the Russian Orthodox Church, but observed their pagan rites privately. A 16th century German diplomat traveling down the Volga, Adam Olearius, noted, “All those who live around Kazan are pagans, for they are neither circumcised nor baptized.”

Mari beliefs are animist, meaning that inanimate objects were seen to have spirits, and not just humans and animals. To the pagan Mari, the world was occupied by myriad powerful spirits who dwelt in the rocks, rivers, trees and wind, and although there is a “great god”, his role was originally vague — it was only as a result of intense Christian and Muslim influence from the 18th century onwards that Kugo Jumo became the most important deity to traditional Mari worshippers.

For the most part, though, the entities that mattered the most to the pagan Mari weren’t the spirits or the “great god”, but local spirits of the violent dead called keremets. Half ghosts and half household gods like those of ancient Rome, keremets could offer protection or curses depending on the Keremet in question.

Each village had a sacred grove nearby (think the Godswood in Game of Thrones) where animal sacrifices were offered to the Keremet in exchange for some service — protection in battle if he had been a great general in life — or to appease their wrath if he had been a thief and murderer. From the folk stories of the individual keremets you can build a portrait of those individual communities, their concerns and their histories.

These “People of the Keremet”, as the pagans were sometimes known, were able to survive alongside Christianity, because their faith wasn’t one of constant — daily prayers and weekly church services, for example — but one that was used to solve specific problems. It was therefore very easy for a Mari to consider themselves a Christian, praying before bed while sacrificing a horse, sheep or chicken in the sacred grove in the hope that their cattle might survive the winter.

By the 1860s and 1870s, the traditional Mari faith underwent a period of monothesisation, with keremets and the smaller gods sidelined in favour of the worship of Kugo Jumo as the supreme deity.

The new evangelical movement — called Kugo Sorta (Great Candle) — impacted on the Mari lifestyle in a way the old faith hadn’t, instilling in them the need to live “cleanly” and “without sin”, and rejecting tobacco, alcohol and caffeine. It also called for an end to blood sacrifice, which was stretching the resources of poor communities to breaking point. Instead of a butchered horse, the worshippers would leave a cake in the shape of a horse.

The isolation of the Mari was coming to an end as the forests around the Volga River were steadily depopulated by hunters and loggers. Roads opened up rural communities to missionaries and magistrates, and the encroaching Russian peasants settled villages in the surrounding area. An official campaign of “Russification” quickly followed, with the suppression of the Mari language and instruction in Russian Orthodox worship.

Kugo Sorta had turned its respect for nature into an Amish-like retreat from the increasingly industrialized world: the Mari were forbidden from wearing artificial colours, using medicines in all but the direst circumstances, and using any factory-made goods.

The aims of this religious reformation were twofold: it offered moral certainty in a rapidly changing and sometimes frightening world, and the transformation of their paganism into a more palatable monotheism was the best chance their faith had of finding official recognition and therefore survival.

In 1890, the Mari presented a display on their beliefs at the Kazan Scientific and Industrial Exhibition and wrote letters to the Tsar (in vain) reassuring him that there was nothing disreputable about their belief.

As they saw it, this was the only way that their religion might stand a chance of survival but it was resisted by the Russian Orthodox Church, and by many true believers within the Mari community who saw the new creed as a betrayal of their ancestors.

The Mari reformers had good reason to be afraid. Well into the 19th century, conflict between Russian Christians and their non-Russian neighbors had led to accusations, and executions, for witchcraft — and in the west of Russia bloody massacres, forced evictions, arson and theft were being targeted against the empire’s Jewish communities. Nonetheless, the Kugo Sorta movement not only allowed Mari paganism to resist the encroaching Russian state and church but helped the faith to grow among the Mari.

By the time of the Russian Revolution, they were represented by a political organization called Marii Ushem (Mari Union), which saw the Bolsheviks as the best chance of protecting their ancient way of life from Christianity.

Despite the creation of a Mari Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic within the USSR, the coming of the Communists was a false dawn and under the rule of the tyrant Joseph Stalin, Russian was enforced as the official language, Mari religious beliefs were pushed to the margins, and Mari culture was suppressed.

But their faith endured as Mari snuck out at night to worship at the sacred groves and the Mari reputation for sorcery did too. Urban legends circulated the Soviet Union that a house made from the wood of a desecrated grove had burnt down, that a man who kicked a soup pot was paralyzed by the cook’s curse, and the Mari manager of a collective farm struggled to find inventive ways to report the deaths of his livestock which he accepted had been killed by witchcraft.

With the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, Mari paganism underwent a revival hand-in-hand with Mari nationalism. Despite its low numbers in comparison to the other religions followed by Russia’s many people, the Mari Native Religion was recognized as one of the three official religions of the Russian Federation alongside Christianity and Islam. 300 sacred groves and holy places were granted protected status, and blood sacrifice returned openly.

Pagan priests, called karts, became extremely active in politics and environmentalism. Much like Kugo Sorta, this movement also has a name — Oshmarii-Chimarri (White Mari or Pure Mari) — but its stridently nationalist tone led to a backlash from Russians in the republic, whose opposition parties are characterized by their staunchly anti-pagan and pro-Russian rhetoric.

The modern Mari faith is not the same religion that it was 400 years ago, before the coming of Ivan the Terrible. Its priesthood is strictly hierarchical and answerable to a High Kart, its keremets and myriad little gods have disappeared before a single god and a clearly defined pantheon of eight lesser gods, and even pagan households have images of Orthodox saints on their walls.

But the groves remain sacred, the fires are still lit, and the forest is very much alive.