In the early 20th century, 33 striking portraits of native American culture

In the early 20th century, 33 striking portraits of native American culture

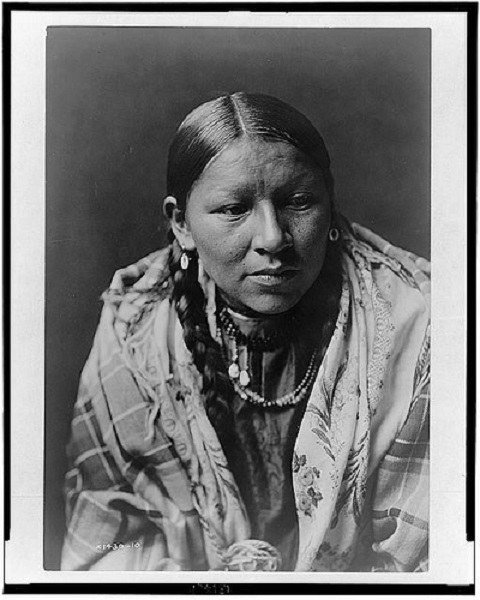

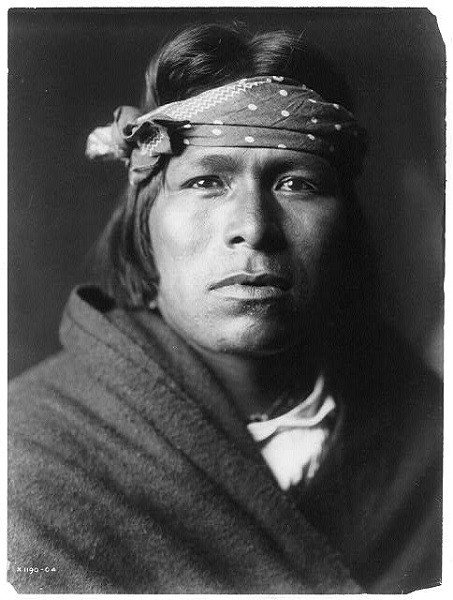

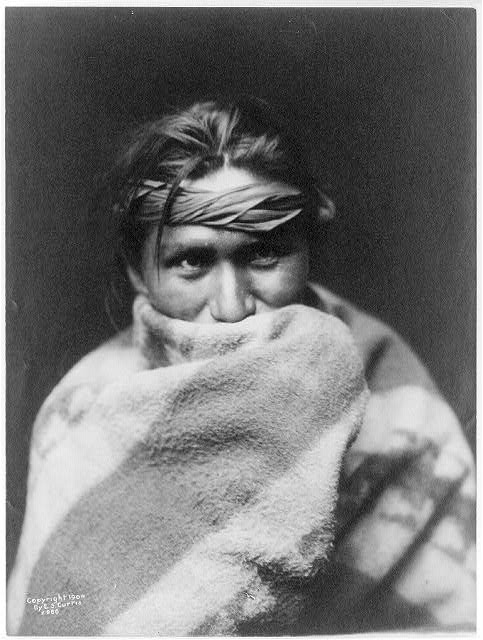

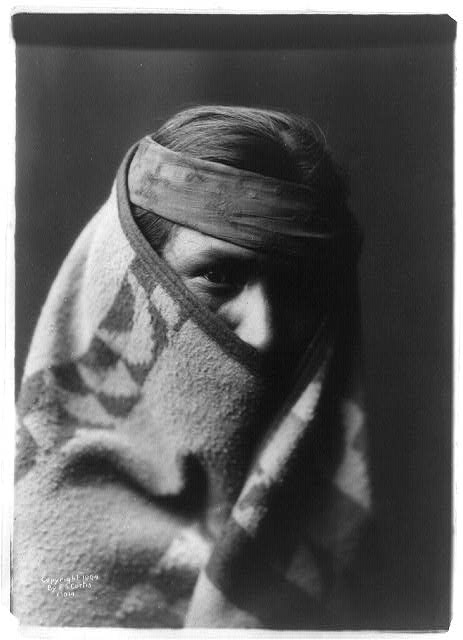

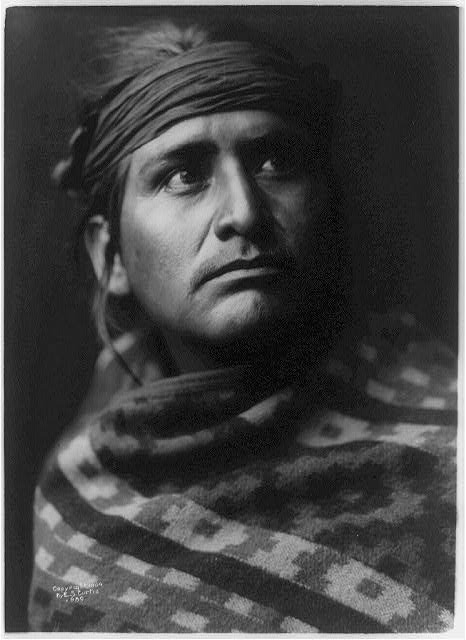

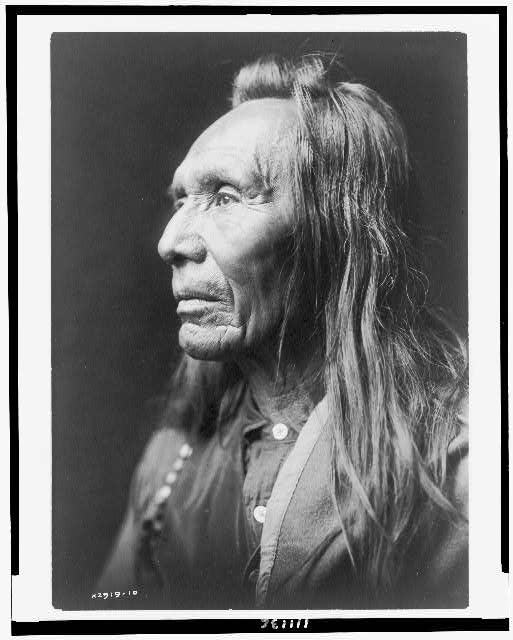

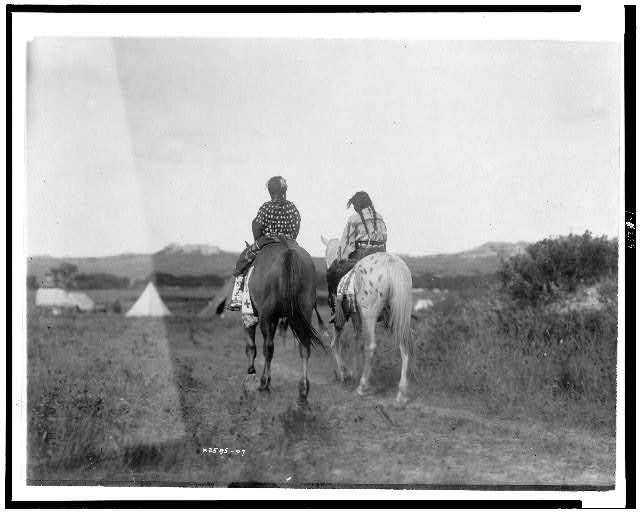

Photographer Edward Curtis embarked on a journey in 1900 that would inspire the work of his life: he decided to accompany anthropologist George Bird Grinnell on a trip to Montana to photograph the Sun Dance, a practice of the Blackfoot Indians. He travelled to Arizona from there, photographing the Hopi tribes.

These trips marked the beginning of Curtis’ most ambitious project: an almost comprehensive record of the indigenous peoples of America and their rapidly disappearing way of life.

Six years later, J.P. banker and financier. Morgan — who initially informed Curtis that he would not be able to fund his project — allowed Curtis $75,000 to produce a 20-volume compendium called The North American Indian.

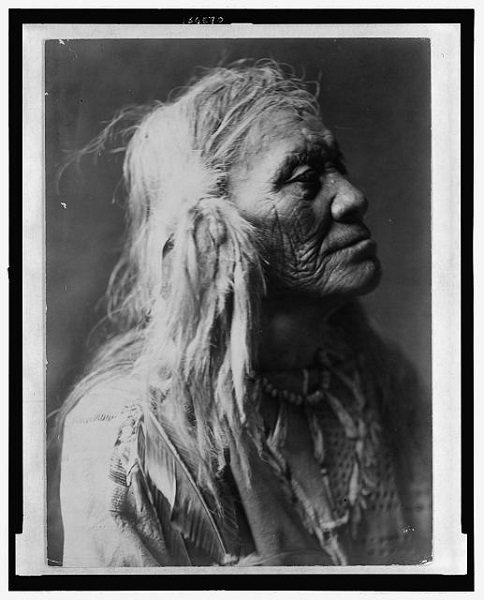

In the introduction to the first volume, published in 1907, Curtis wrote, “The information that is to be gathered… respecting the mode of life of one of the great races of mankind, must be collected at once or the opportunity will be lost.”

Following that first volume, Curtis’ work ultimately took 30 years to complete and ruined his health along the way. He hoped to photograph every indigenous tribe in America — a nearly impossible task — but he certainly came close.

The project yielded 40,000 pictures of 100 tribes. He reproduced around 2,200 of them for The North American Indian, published between 1907 and 1930. He furthermore recorded songs and speech from about 80 tribes, all in their native languages.

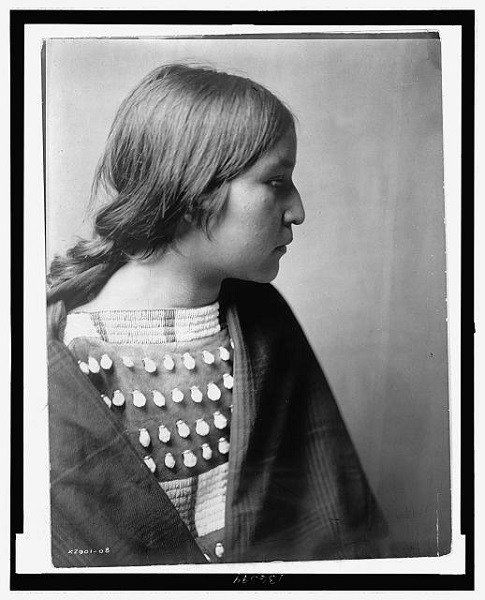

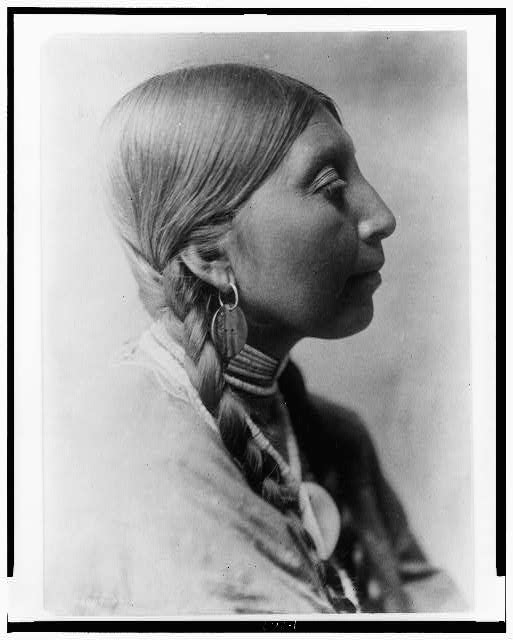

Though Curtis romanticized Native American culture (he often photographed his subjects in ceremonial wear that was not regularly worn and used wigs to hide modern hair cuts), he was an outspoken opponent of the often devastating use of relocation and reservations, and his photographs remain one of the only historical documents that give insight into the lives of a people-driven nearly to extinction by colonization.

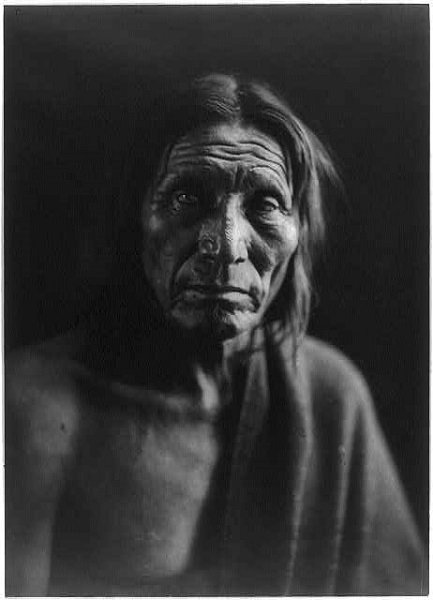

The Klamath Tribes, which also include the Modocs and the Yahooskin, didn’t encounter a white person until 1826, when a fur trapper wandered into their territory. Just 28 years later, in 1864, the tribes agreed to cede 23 million acres of their land in exchange for a reservation. In 1954, an act of Congress ended federal recognition of the Klamath tribes, which meant that they lost their reservation and the accompanying human services. Their rights as a federally recognized tribe were not restored until 1986.

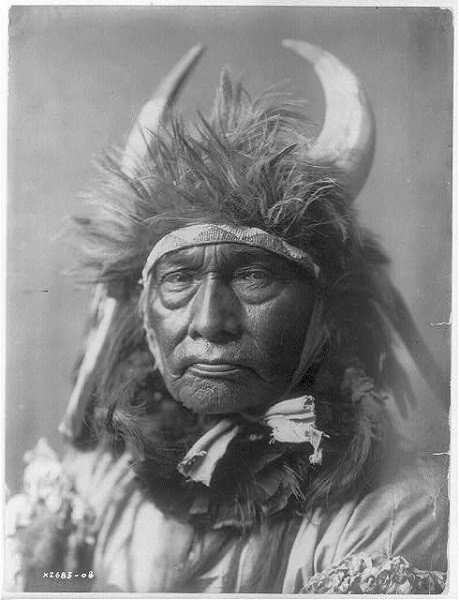

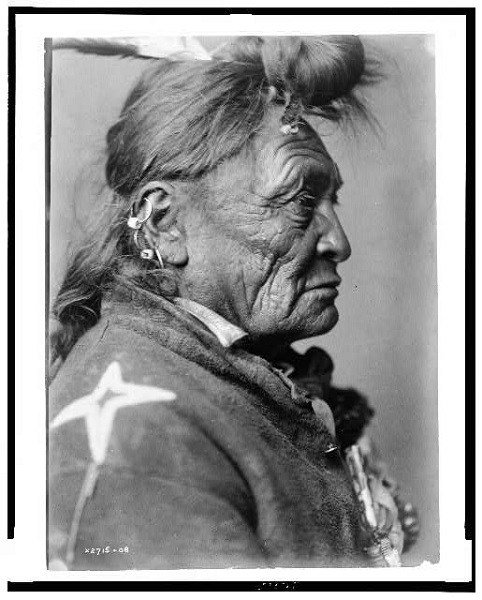

Plains Indians primarily wore the headdress, called a horned war bonnet, seen to the left. They made these headdresses from a buffalo with the animal’s horns attached.

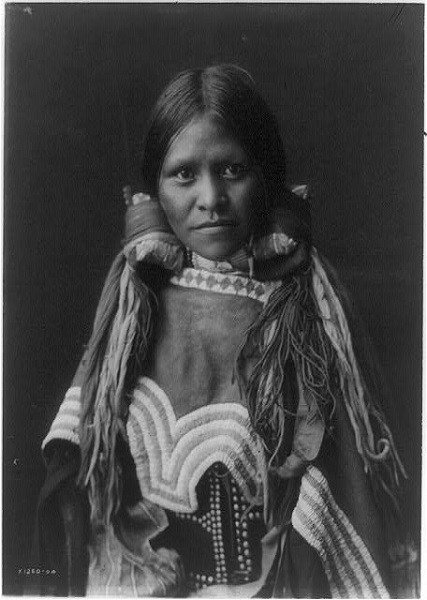

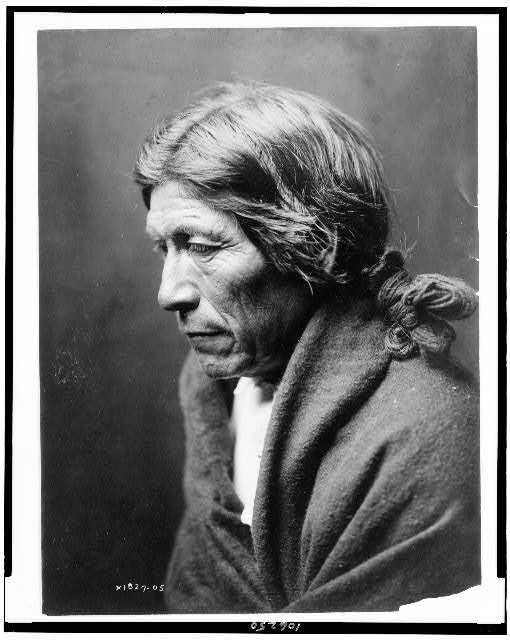

The Jicarilla people are members of the Apache nation, and originally resided in Colorado and New Mexico. The Jicarilla posed a strong resistance to European encroachment on their lands: They fought relocation in conflicts with the U.S. Army like the The Battle of Cieneguilla. Eventually, President Grover Cleveland signed an executive order establishing the Jicarilla Indian Reservation in New Mexico in 1887.

As soon as the 1860s, while the federal government systematically forced Native Americans onto reservations, the it also began setting up day schools near the newly formed reservations. The government intended for these schools to re-educate and “civilize” young Indian children. By 1878, a U.S. Army Lieutenant named Richard Henry Pratt had set up boarding schools dedicated to re-educating Native American tribes. School rules forbade students from speaking their native languages, and mandated that they had their hair cut, wear Western attire, and that they practice Christianity. Between 1880 and 1902, 25 of these boarding schools were built, with about 100,000 students passing through their halls — usually brought there against their will. Despite these techniques of assimilation, many tribes retained some elements of their former identities and continued to pass down their cultural traditions, often in secret.

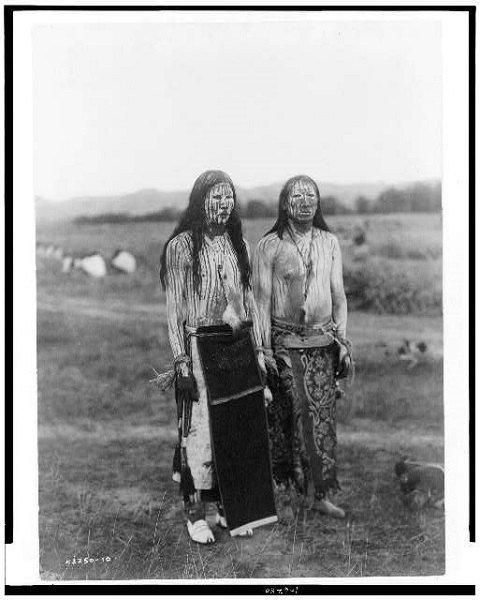

The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 established the first Cheyenne reservation in Colorado, long before Edward Curtis began his project. However, during the Gold Rush, the government revoked that treaty and in 1877 forced the Cheyenne onto an Oklahoma reservation. Some Cheyenne resisted, and escaped to Montana. In 1884, the federal government established a reservation for them there as well.

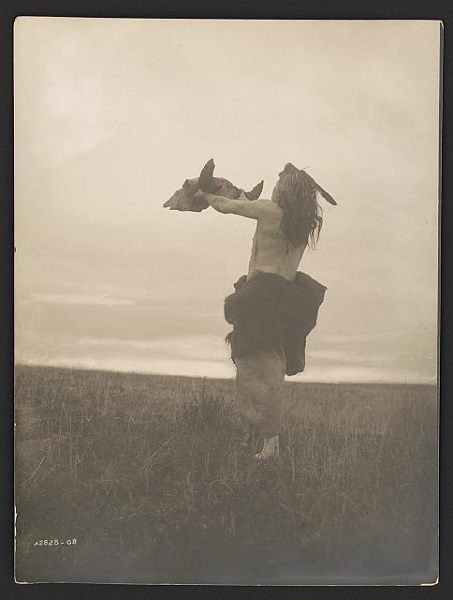

Cheyenne men wearing body paint for the Sun Dance, a religious ceremony practiced by the Plains Indians — such as the Cheyenne, Sioux, and Cree tribes — in the 19th century. Tribes perform the ritual at the Summer Solstice, and it includes dancing, singing, and sometimes self-mutilation — a young man participating in the ceremony may dance around a pole to which he is attached by a rawhide thong pierced through the skin of his chest. For this reason, and in an effort to suppress Indian culture and religion, the practice was banned in the U.S. and Canada. It wasn’t until Congress passed the American Indian Religious Freedom Act in 1978 that Plains Indians could openly practice the Sun Dance.

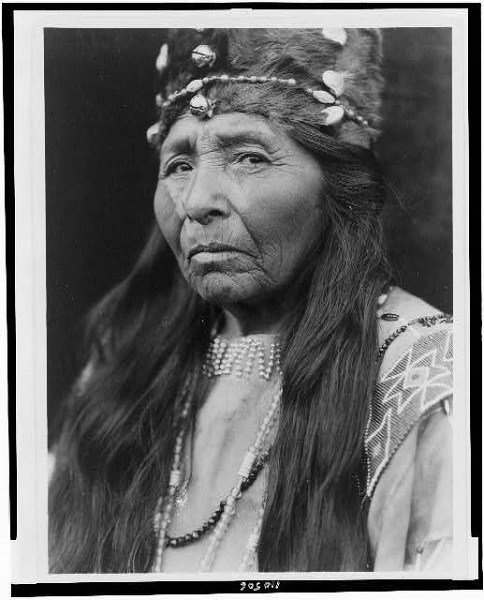

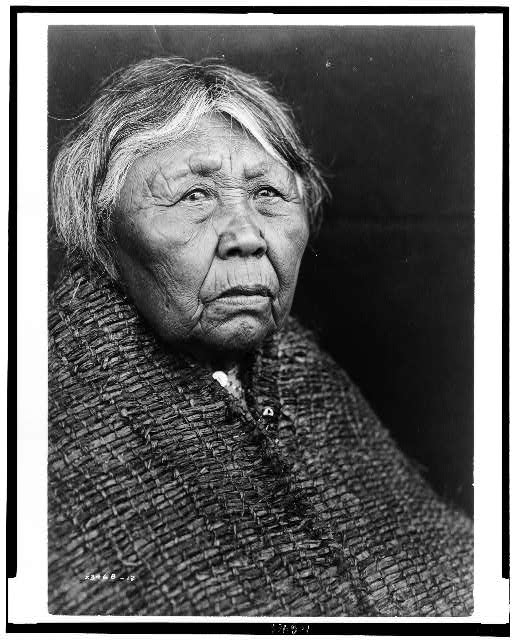

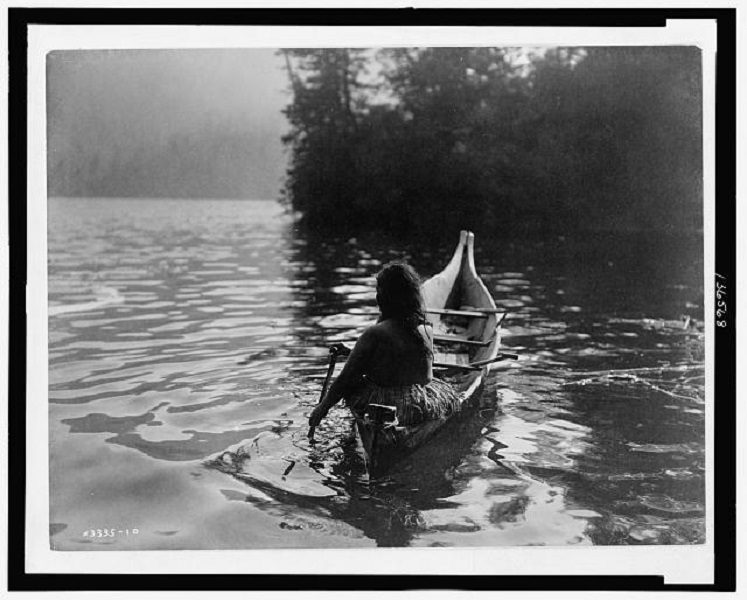

The Skokomish people lived in the Hood Canal region of Washington State. Pacific Northwest Indian tribes practiced the Potlatch, a traditional feast held on special occasions. In an effort to suppress Indian culture and traditions, Canada banned the Potlatch in 1884 as part of its Indian Act. The government didn’t repeal the ban until 1951.

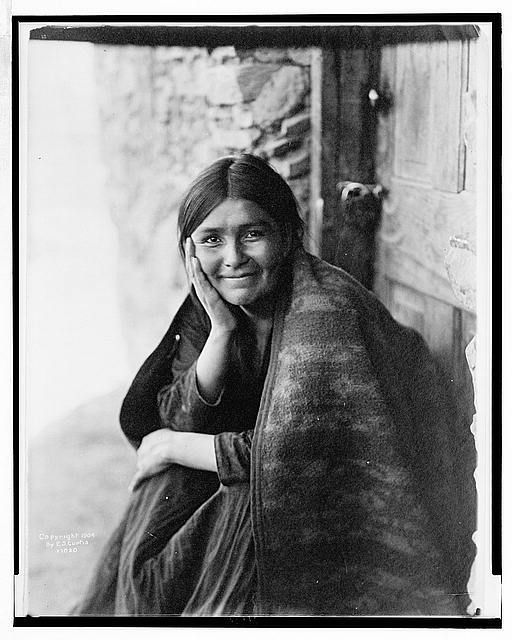

The Zuni people (also known as the Anasazi) are Pueblo Indians who reside in New Mexico. The name Pueblo comes from the adobe settlements they have lived in for more than 1,000 years.

The Acoma tribe has lived on the Acoma Pueblo in New Mexico for more than 800 years.

The Najavo Nation is currently the second largest federally recognized indigenous tribe in America. In 1864, around 9,000 Najavo people were forced to relocate to Fort Sumter, New Mexico on foot in the “Long Walk.” The Navajo who survived the journey were forced to live in internment camps. In 1868, a treaty between the U.S. government and the Navajo leadership established a reservation on their ancestral lands, and the once-displaced people were allowed to return to their homes.

Today, the Najavo reservation spans 14,000 miles between Arizona and New Mexico and their population exceeds 250,000 people.

During WWII, the Marines recruited several Navajo “code-talkers” to create a code for the military that the Japanese could not break.

In 1870, the U.S. government established the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation for three tribes — the Arikara, Mandan, and Hidatsa — after they joined forces following tremendous losses in population from Smallpox epidemics and forced relocations that brought the three tribes closer together.

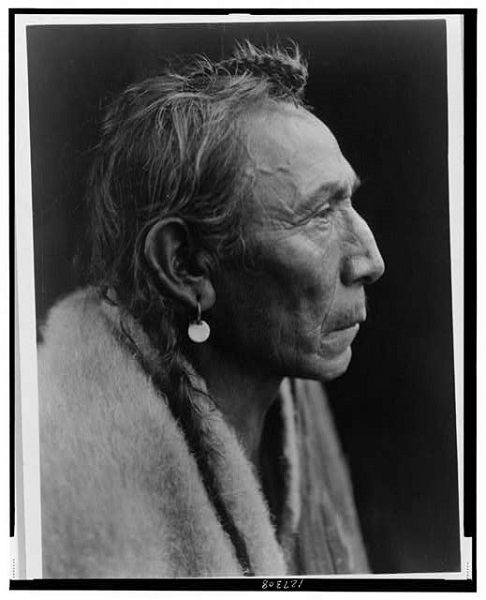

18th century French-Canadian fur traders called this tribe the Nez Percé (“pierced nose”). The tribe, which originally called itself the Niimíipu, eventually adopted the French name. In 1877, the Nez Percé split into two groups: Those willing to relocate to a reservation and those who refused. Led by Chief Joseph, nearly 3,000 Nez Percé tried to flee to Canada in June 1877, but the U.S. army pursued and forced them to surrender in October of that year. Today, their reservation is located in central Idaho.

The Wishram people, or Tlakluit as they were known to each other, traditionally lived along the Columbia River in Oregon. In 1855, the government forced them to sign treaties that required them to cede most of their land. They were absorbed into Yakima Indian Nation in Washington state, where they live to this day.

In the 1860s, cattle ranchers began to lay claim to the land in the Kittitas Valley, Washington. The growing industry dislocated Native American tribes living there. The Kittitas dispersed to the Yakima Valley, until they too were absorbed into the Yakima Indian Reservation.

The Cayuse people of Oregon and southeastern Washington merged with their close relations, the Umatilla and Walla Walla tribes, in 1855, after a treaty forced them to cede most of their ancestral land for the 250,000 acre Umatilla Indian Reservation in Oregon, where they still live today.

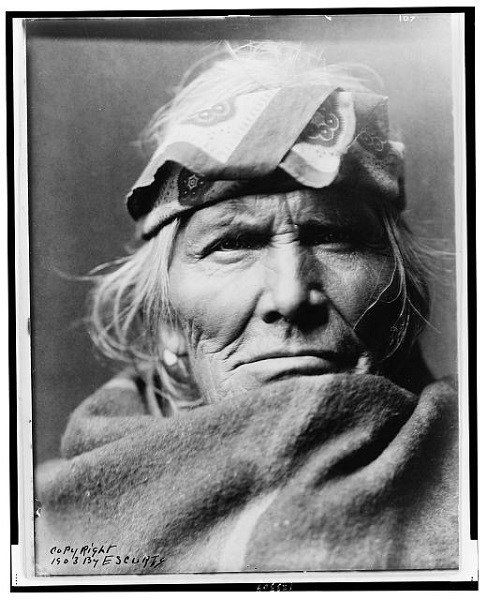

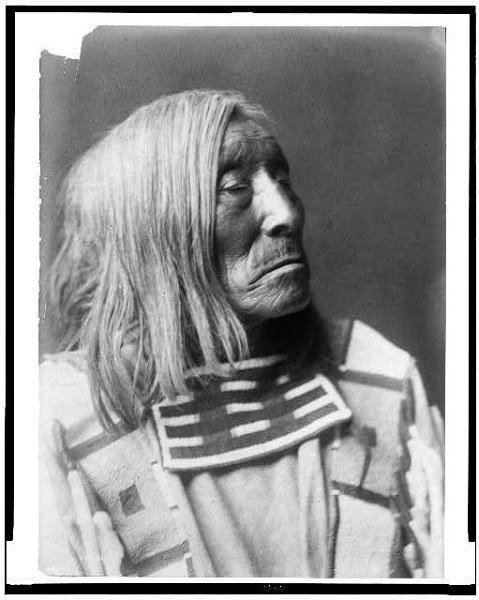

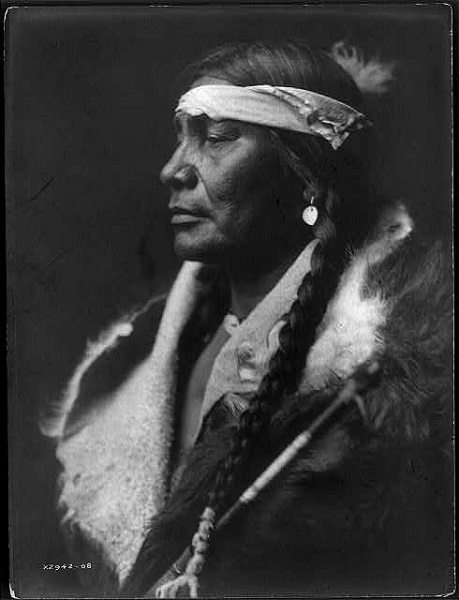

The name Sarsi was most likely given to this tribe by the Blackfoot people, with whom they had a long territory dispute. They now prefer to go by their own name, the Tsuu T’ina, and their official reservation is located in Alberta, Calgary, where the tribe originally lived before moving to the plains of the United States.

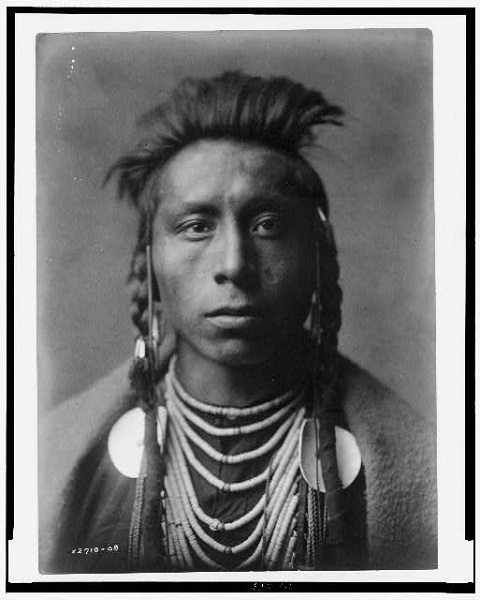

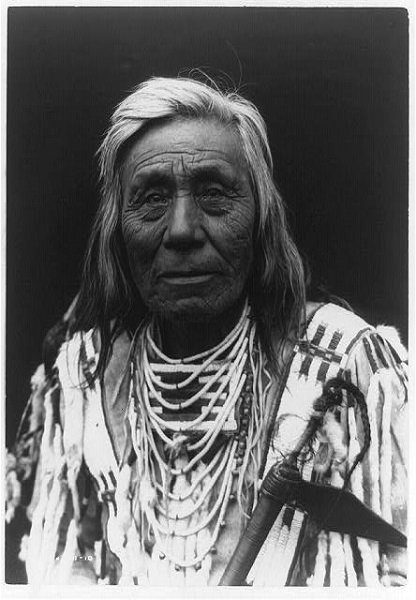

Edward Curtis wrote that the Asparoke, another name for the Crow people, first began treaty negotiations with the U.S. government in 1825. By 1868, “they relinquished their claim to all lands except a reservation…This area has since been reduce be cession to about 2,233,840 acres.”

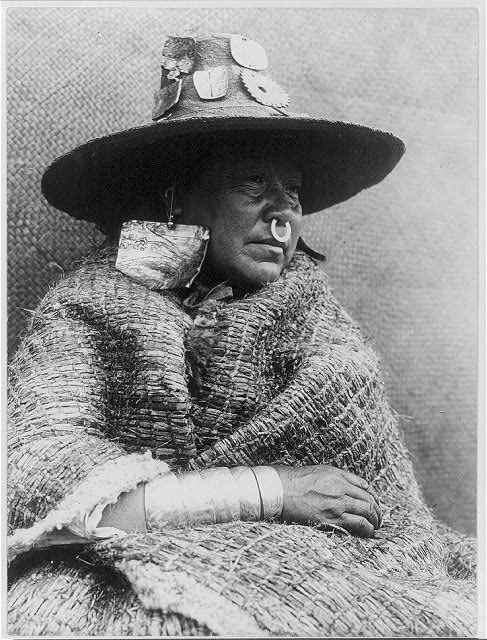

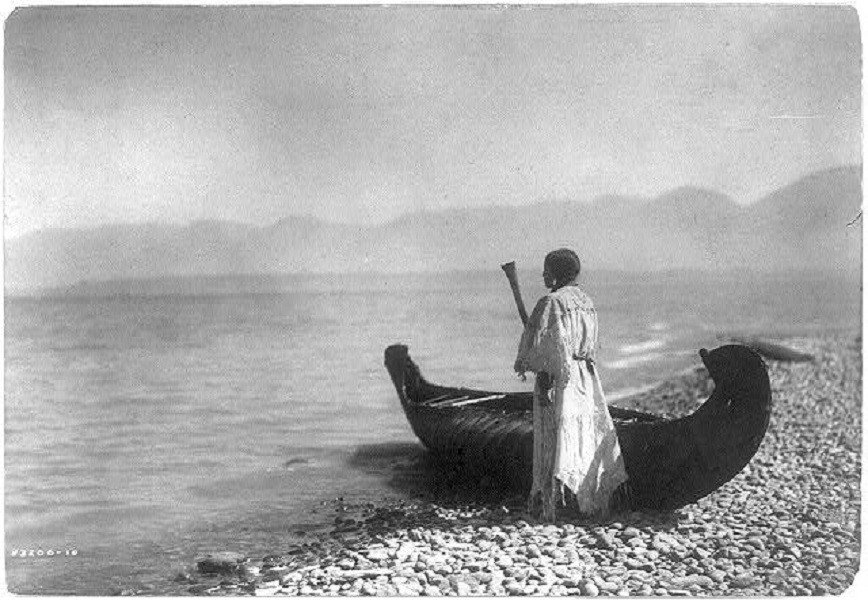

The Native American tribes inhabiting Clayoquot Sound are the Ahousaht and the Hesquiaht. They lived along the west coast of Vancouver. Around 1856, European settlers introduced diseases like smallpox and measles to this area, reducing the indigenous population in the Clayoquot Sound by 90 percent.

The Nakoaktok belong to the Kwakiutl group of Pacific Northwest indigenous peoples. They reside in British Columbia and Vancouver Island. From 1830 to 1880, the Kwakiutl population dropped 75 percent due to diseases that European settlers introduced to their tribes.

Though the Kutenai people of British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest first encountered European settlers in the early 1860s during the Gold Rush, they never signed a treaty with the federal government. In 1974, the remaining Kutenai tribe declared war on the United States. Though the tribe remained peaceful, the display earned the attention of the government, which gave the tribe 12.5 acres of land that now constitutes the Kootenai Reservation.

The federal government tried to get the Atsina people, otherwise known by their French name of the Gros Ventre, to share a reservation with the Sioux in 1876, but the two tribes considered each other enemies and the Atsina refused to go. In 1888, the government established the Fort Belknap Reservation in Montana as their official territory.

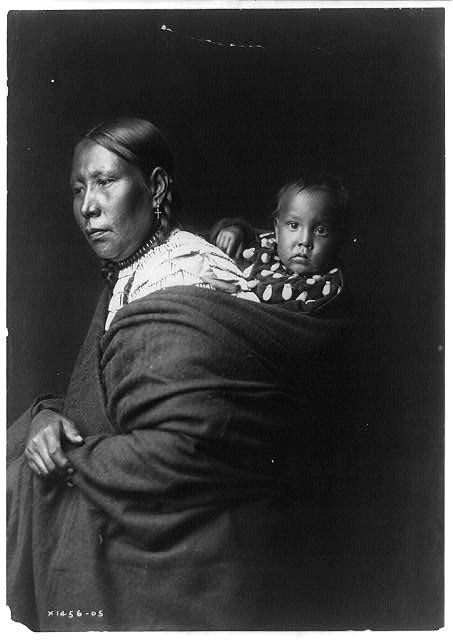

An Oglala Lakota woman with her child. The Oglala Lakota people make up part of the Great Sioux Nation. The majority of them now live on the Pine Ridge Reservation, which Congress established in 1889 after it divided the Sioux Nation onto five different reservations. The Sioux Treaty of 1868 guaranteed the Lakota people ownership of the Black Hills in South Dakota, but the land was seized in 1877 after gold prospectors began crossing into the reservation. To this day, the Lakota continue to fight for the return of their land.

The Tewa are a group of Pueblo Native Americans who joined the Hopi people on the Hopi Reservation in Arizona following a 1680 revolt against Spanish settlers.

The Teton Sioux encountered Louis and Clark’s expedition in 1804, when the tribe refused to allow the explorers to pass through their territory without, according to National Geographic, paying a “toll of a tobacco” that would guarantee they could continue their travels unimpeded.

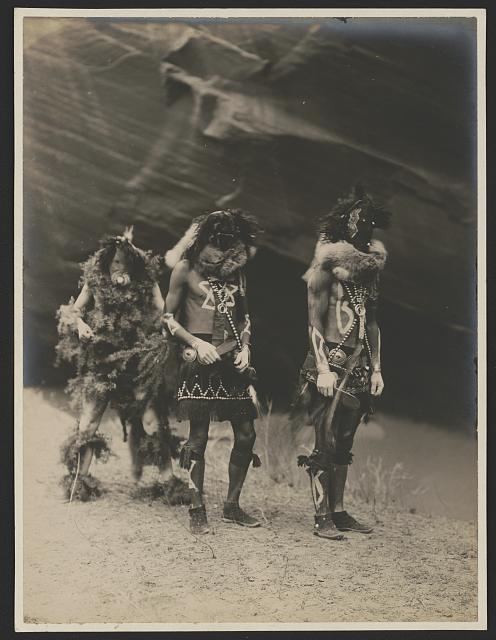

Navajo men dressed as the war gods Tonenili, Tobadzischini, and Nayenezgani, for the Yebichai ceremony, otherwise known as the Night Chant, 1904.

Subscribe to our newsletter!